By: Henning Melber (Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation)

Originally published 15 April 2016 [LINK TO ORIGINAL]

The forced removal of the inhabitants of Windhoek’s Main Location to the township Katutura provoked organized mass protest culminating in a massacre on 10 December 1959. Today a public holiday commemorates this act of resistance. The former location became a synonym for African unity in the face of the divisions imposed by Apartheid. But little is publicly known on the life there.

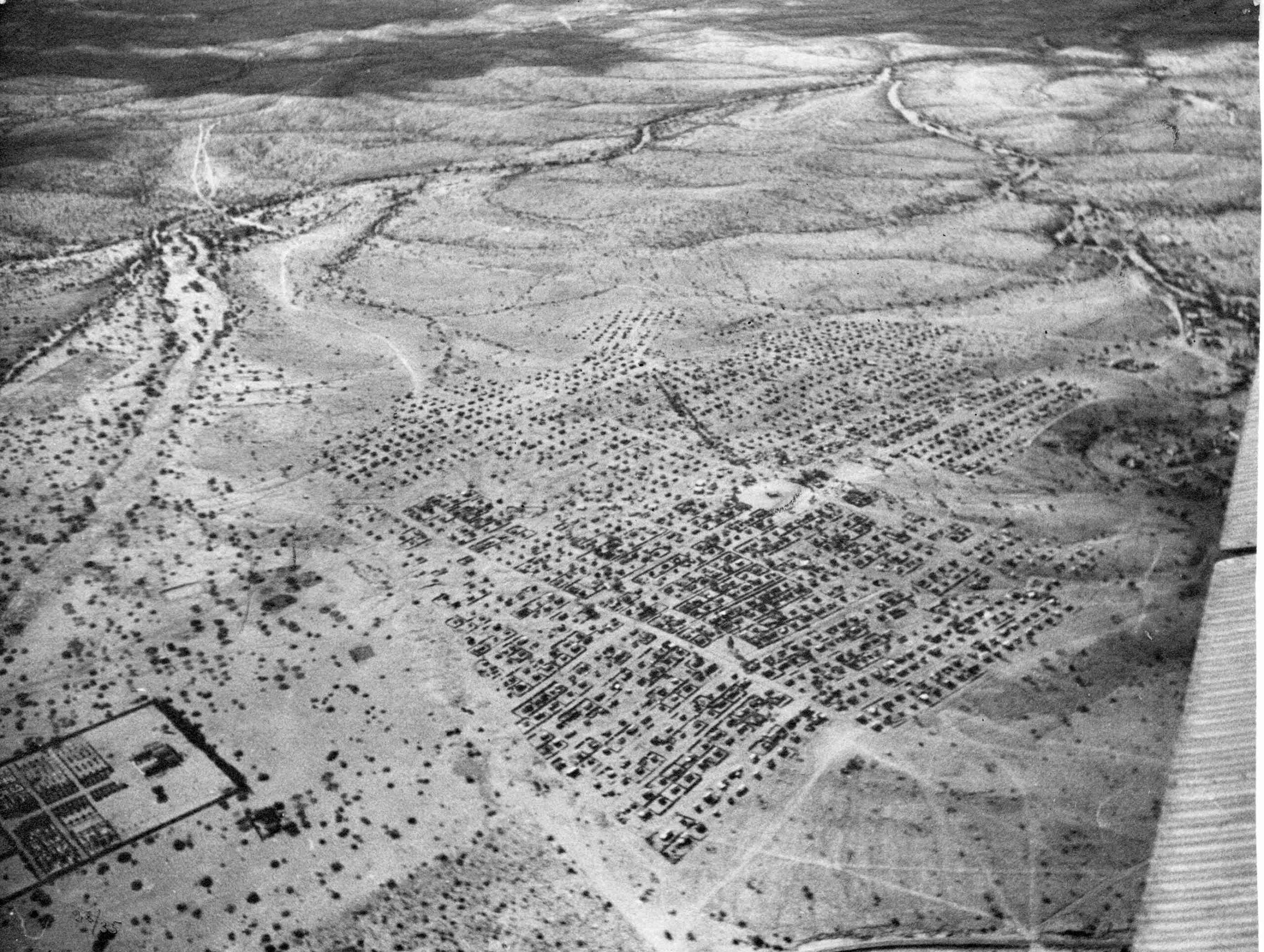

The Old Location has mainly remained alive in the memories of those once living there. For the outside world, it is two generations later largely a “terra incognita”. The Anglican clergyman Michael Scott was the only known intruder from the outside. In 1948 he camped for two months in the dry riverbed of the Gammams River bordering to the settlement. He assisted the Herero leadership in petitioning the United Nations, alerting to the plight of the Namibians. It was then when Chief Hosea Kutako stated: “O Lord, help us who roam about. Help us who have been placed in Africa and have no dwelling place of our own. Give us back a dwelling place.”

The Old Location plays a prominent role in the “patriotic history” presenting the formation of Namibia’s modern anti-colonial resistance leading to an armed liberation struggle. The refusal to be voluntarily relocated to the newly erected township of Katutura, culminating in the massacre of 10 December 1959, played a crucial role in the consolidation of political organizations, and especially the formation of the South West African People’s Organisation (SWAPO). However, most of the published life histories of Namibians at that time politically engaged (most prominently John ya Otto’s Battlefront Namibia, but also Sam Nujoma’s Where Others Wavered), do not refer in any detail to the daily life and interaction in Windhoek’s old township. These biographies were mostly from those who were on contract labour and therefore not living there. Contract workers employed in Windhoek had their own compound at “Pokkiesdraai”, in the vicinity of today’s Northern industrial area. As a result, the role of residents not affiliated to the contract workers movement organized in the Ovamboland People’s Organisation (OPO), but rather in the South West African National Union (SWANU) or the Herero Traditional Council, remains inadequately recognized.

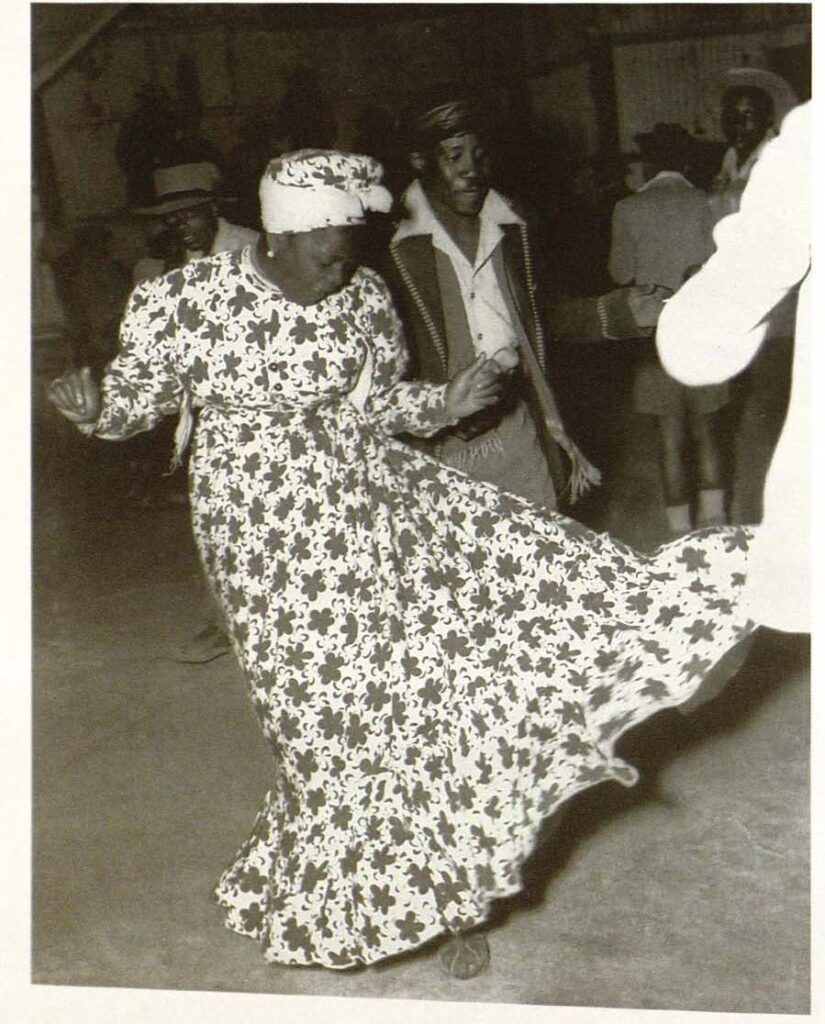

“Human Rights Day” celebrated internationally on 10 December is now as “Women’s Day” a Namibian public holiday. It commemorates the Windhoek massacre, in which at least eleven people were killed when the police opened fire at an unarmed crowd, and in particular pays respect to the courageous women leading the boycott and protest. One of them, Anna (“Kakurukaze”) Mungunda was shot and killed while trying to set fire to the car of the location’s superintendent. She is honored with a grave at the Heroes Acre. But no other efforts were made by the Namibian state to encourage further restoration of memory. Many of those in middle and higher government and civil service ranks now living in Hochland Park are hardly aware that their homes have been erected on the grounds of the Old Location, of which nothing but a steel bridge over the Gammams riverbed in Windhoek West (and the dilapidated building of a former “native store” nearby), a few grave stones and a small, hardly known and visible memorial site reminds of its former existence.

More than half a century since the Old Location’s closure one cannot reconstruct and present from the outside the full story of the place, its people, their interaction with each other and with the authorities. The assumed realities had so far occasionally in the “heroic narrative” tradition been at times a romantic projection for “good old days”, which somewhat ignores the Apartheid realities of the time. The forms of social life were positively contrasted with the newly constructed township outside of Windhoek, which accordingly was called Katutura (“a place where we do not stay”).

The ambivalence of the former place of living, where the poor material conditions contrasted with the social spirit and interaction, is captured by a remark of Zedekia Ngavirue (“Dr Zed”, as he is called with respect these days). He was the first social worker employed there (and later sacked) in 1959/1960, a co-founder of SWANU and the co-founder and editor of the South West News/Suidwes Nuus. As the first local African newspaper it was established soon after the shootings in December 1959 and published during 1960. Dr Zed then left for studies in Sweden and became engaged in exile politics. As he observed in retrospect: “It was indeed, when we owned little that we were prepared to make the greatest sacrifices.”