By: Kletus Muhena Likuwa (University of Namibia)

Originally Published 19 August 2016 [LINK TO ORIGINAL]

Youths in Kavango East & West played a central role in mobilizing communities against colonial control; however, little is written about these political experiences. Instead, there is a growing worry that youths are falling short of expectations as central agents for sustainable economic development with in their communities. This article re-assesses the history of youth political experiences under colonialism and apartheid, as well as their mobilization for the independence of Namibia.

Colonial control

The Native Commissioner who was posted to the Kavango in 1921 acted as an agent of the South African administration with regard to improving and regulating the existing flow of Native Labour by means of registers, passes, medical examinations. He also used his influence to prevent serious crimes, including witchcraft. His task was also to maintain amicable relations with the Portuguese Authorities in Angola. He meted out monetary fines and public floggings towards people causing veld fire, killing of wild animals, etc. The enforcement of laws protecting wildlife prevented the Kavango people from their previous easy access to these local resources, resulting in economic and social hardships for families who soon became a breeding ground for political consciousness and mobilization for SWAPO.

Early SWAPO Mobilization

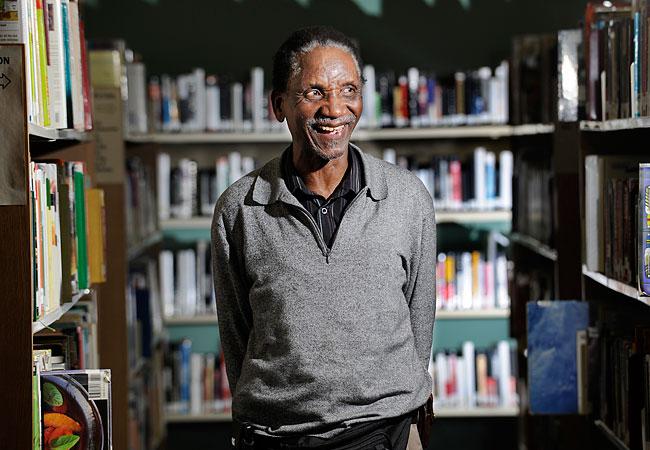

Such ensuing hardships and control compelled men, many of them youths, into the exploitative contract labour system, however, many were mobilized by OPO and later SWAPO activists. Key among these early political leaders was David Ausiku, also called Lyangurungunda.

Ausiku, born in 1936, was among the first SWAPO leaders in Kavango who mobilized the local people. As a result of this activism, the youth began to show pro-SWAPO and anti-apartheid ideas at the community meetings that were held all over the Kavango in the late 1960s. It has been remarked that during the 1967 Odendaal Commission for proposing apartheid Bantustans, the administration noted increasing spread of pro-SWAPO ideas and frontier ‘terrorists’.

By 1973 Kavango people became increasingly mobilized to join SWAPO through Muzogumwe, meaning ‘One Move’, a pseudonym for SWAPO under David Ausiku’s leadership. As a result of the mobilizations of the local people by the returning youth workers, folks began to express their disillusionment with the contract labour system, especially against the exploitative recruitment operator, SWANLA.

Later SWAPO Mobilization

By the mid-1970s, sport became the alternative medium through which to encourage youth political activism in Kavango. Youths gathered or travelled in the name of sport to discuss political issues. However, by the 1980s, NANSO became a prominent organization for SWAPO mobilization. NANSO, formed in 1984, had by the end of 1987 established a regional committee in the Kavango following a letter of request from one of its national leaders, Ignatius Shixhwameni, to the student leaders in the region.

The end of 1987 saw a rapid increase of Kavango student activism in national politics through support and participation in the national school boycotts of 1988. Since students had no say in their education, NANSO began to organize class boycotts, mobilization against food, transportation, school and hostel fees, as well as against corporal punishment and unfair treatment.

Kavango youths linked student rights issues to national politics. Youths felt a lack of participation in the administration of schools, and they also experienced Koevoet’s disruption of the teaching process because of assaults and arrests of students for wearing SWAPO and NANSO t-shirts.

Namibia’s First Elections

The late 1980s also saw the youth in the Kavango take an active role in the 1989 election campaigns through the uses of posters, placards and t-shirts. This political mobilization often resulted in youth activists getting brutalized. It was reported, for example, that police attendance of political rallies often led to unnecessary use of force, individuals being threatened with abductions of children, and the destruction of crop and houses.

However, the distribution and display of political images by the youths in the late 1980s had great influence on the voting masses in the Kavango. The impact of these political images at public meetings and in more sheltered, private spaces provided an opportunity for NANSO and SWAPO youth activists to engage in a political dialogue and debate with people they met.

SWAPO’s victory in Kavango in the 1989 election was a turning point for SWAPO’s overall national victory in the first elections. Considering that out of all former homelands and all 23 electoral districts, SWAPO only won in Kavango and Ovambo homelands, it is fair to assert that SWAPO’s 1989 election victory in the Kavango was perhaps the most significant electoral district victory of nationalism over regionalism.