By: Minna Saarelma-Paukkala (University of Helsinki)

Originally Published 9 September 2016 [LINK TO ORIGINAL]

“Edhina ekogidho” is an Oshiwambo saying which means that names are links. Personal names indeed connect people to their history in many ways. The names of the Namibians are like an African quilt with many colourful pieces of textile: African names, biblical names, European names.

Uusiku and other old names

Personal names had an important role in traditional Ovambo culture, as the name was seen as an essential part of the person. When children were born, they were first given temporary names, which often referred to the time of the birth, e.g. Uusiku ‘night’, or Nandjala ‘hunger’. The real name was given a few weeks later by the father. The child was typically named after a friend, a neighbour, or a relative of the father.

The relationship between people sharing the same name was especially close. It was believed that sharing the same name also meant sharing the same personality. To be asked to become a namesake for a newborn child was the greatest honour that one could experience in Ovambo community.

Sometimes names also reflected the feelings of the father: Ndahafa ‘I am glad’, Ndatila ‘I am afraid’. Names could also tell about the future duties of the child. A girl could be named Taatsu, for example, which refers to grinding corn.

Biblical and European names

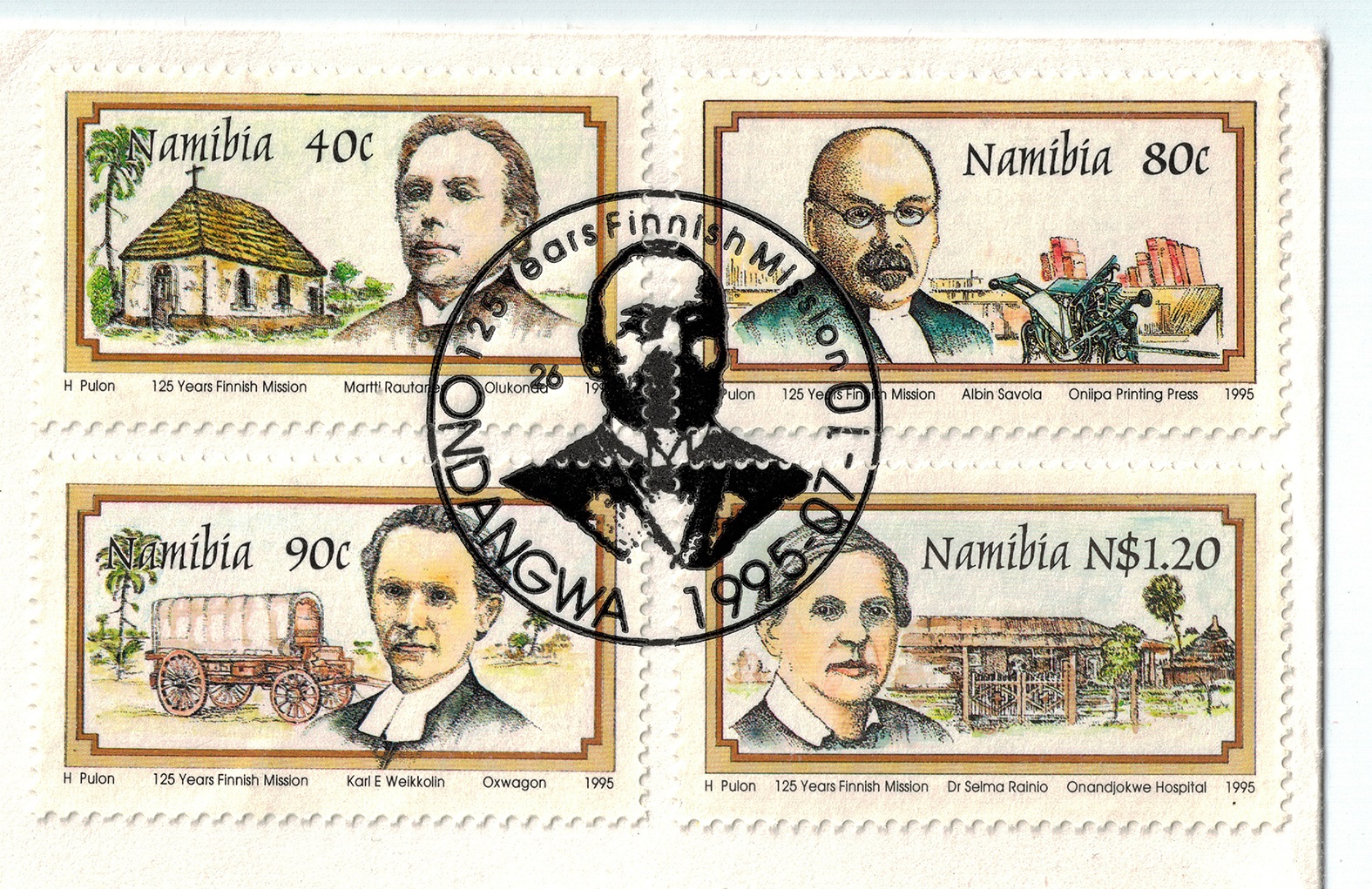

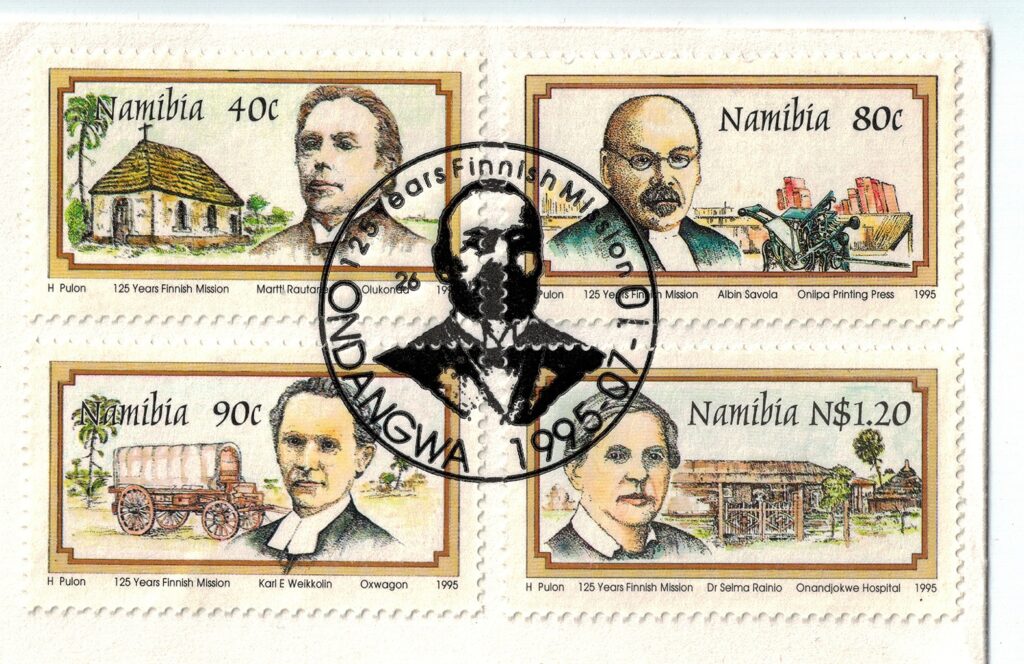

The adoption of Christianity, and the practice of giving new names at baptism, led to a rapid change in the Ovambo naming system. In 1883, the first six Ovambo men were baptised at Omulonga by the Lutheran missionary Tobias Reijonen from Finland. Their names – Moses, Elias, Abraham, Jakob, Tobias and Johannes – were all taken from the Bible, and one of the converts was Reijonen’s namesake.

The first baptisms in the Ndonga royal family took place in 1901, when two nephews to the king, Kuedhi and Nehale, were baptised. The former became Albin after the Finnish missionary Albin Savola, and the latter Martin after Martti (Martin) Rautanen. The first baptism of an Ovambo king took place in 1912, when the King of Ondonga, Kambonde kaNgula, was baptised on his deathbed by missionary Juho Wehanen. The king wanted to adopt the name Eino Johannes – the name of Wehanen’s son.

The number of Lutherans grew rapidly in Ovamboland: from 900 in 1900 to 23 000 in 1930. This also meant that biblical and European names spread rapidly. Foreign names were not always adopted as such: the name Wilhelm became Vilihema, and Ester Esitela.

New life, new name

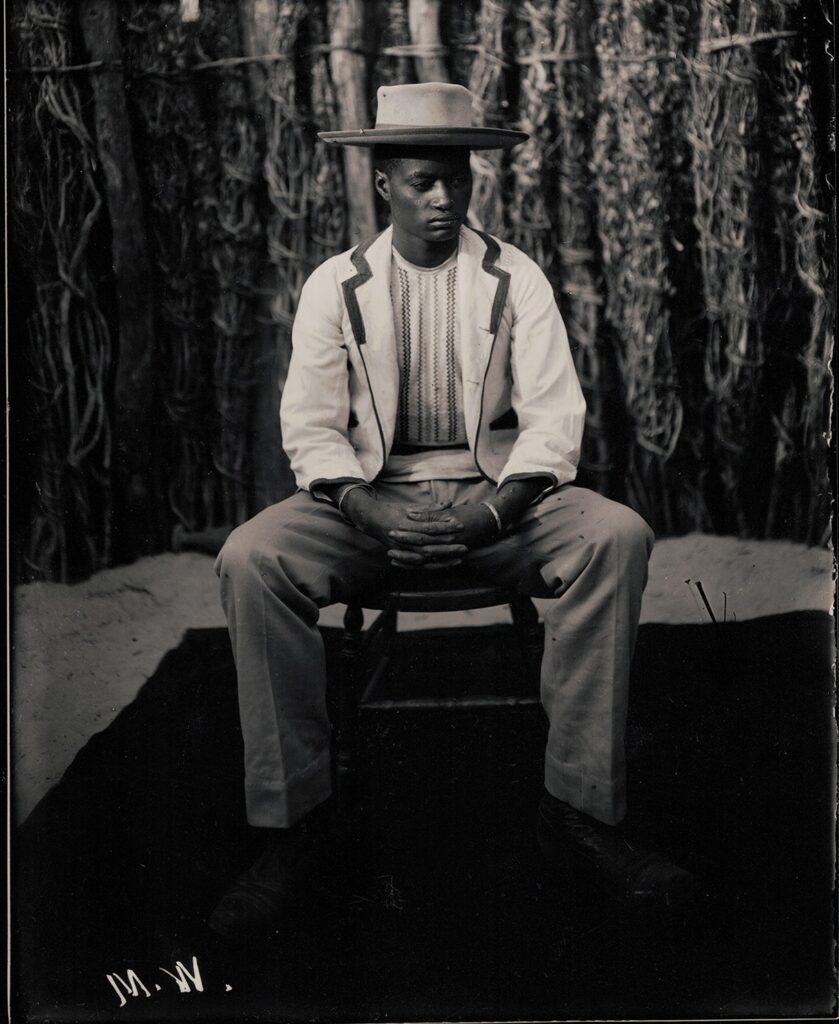

In the early 20th century, most converts adopted foreign names when they embraced Christianity. A new “Christian” name was seen as a symbol of a new life and of abandoning traditional beliefs. At first, Ovambo Christians were ridiculed because of their strange names, but soon this was changed, and the new names became fashionable. They also served as symbols of expected social progress in the colonial society.

The popularity of biblical and European names has most often been explained by the Ovambo namesake custom. A large number of Ovambos have been named after European missionaries or others who were named in their honour. As a result, many European names have been passed on in the society for many generations. A good example is Selma, the most popular women’s name among the Lutheran Ovambos. The original Selma was Dr Selma Rainio from Finland, who founded the Onandjokwe Lutheran Hospital in 1911. It is noteworthy that many European names were adopted because of a friendship – and not because the Ovambos were forced or pressed to adopt them.

Missionaries promoting indigenous names

There was also resistance to the use of foreign names in the early 20th century. As a result, in 1905 two Finnish missionaries, Emil Liljeblad and Heikki Saari, decided to give African names to their daughters, which at that time was unheard of. Liljeblad named his daughter Aune Mtaleni Nahenda, meaning ‘look at Aune with mercy’. By doing this, he wanted to show that Ovambo people need not despise their beautiful indigenous names. Saari named his daughter Kerttu Nekulilo ‘redemption’. These African names caused astonishment both among the missionaries and the local people.

Missionary Walde Kivinen wrote in 1937 that he had encouraged Ovambos to adopt African names, because “otherwise all men here will soon be called Paulus, Petrus and Johannes”. In 1937, the conference of the Finnish missionaries discussed African baptismal names. Heikki Saari defended the use of African names and argued that they could play a part in creating an Ovambo people with a national spirit. The Finnish Mission also published a calendar, Ondjalulamasiku Jomumvo 1938, which included Oshiwambo names (e.g. Uukongo and Nambili), and thus served as a name-guide for Lutheran Ovambos.

Revival of African names

However, it was not until the 1960s that African names were increasingly adopted in Lutheran congregations. They emerged together with the struggle for independence. People in the North wanted to show with their names that they are Africans, and especially Namibians. African names appeared in parish registers when people started to give their children more than one name at baptism. Typically, the first given name was biblical or European, and the other name African, as in Selma Magano ‘gift’.

After Namibian independence in 1990, many Ovambos have given their children African names only, as an expression of their Namibian identity. African names are also frequently used in everyday life. A good example of this is Andimba Toivo ya Toivo, who was earlier known as Herman Toivo ya Toivo. His surname includes the Finnish male name Toivo ‘hope’. As English is the official language in Namibia, English names have also become popular.

The namesake custom is still strong in Ovambo culture, and many people today carry names that were originally adopted from Europeans who once lived in the country. Indeed, the names of the Ovambos reveal a lot about their history. They tell that these people are Namibians, and Christians, and that they have many European friends.