By: Molly McCullers (University of West Georgia)

Original Published 27 January 2017 [LINK TO ORIGINAL]

In April 1945, Prime Minister Jan Smuts attended the San Francisco Conference establishing the United Nations. He spent his time writing two very different documents. The first was the Preamble to the United Nations Charter, which affirmed fundamental human rights and the equality of nations large and small. The second was a document outlining South Africa’s plans to annex South West Africa. This was Smuts’s second attempt at seizing Southwest. He first tried at the 1919 Paris Conference creating the League of Nations but the League turned him down. He responded by playing an instrumental role in crafting the Mandates System, which gave South Africa control over Southwest as a de facto colony subject to international oversight. Now, in 1945, he hoped to finally acquire Southwest once and for all.

In a press release, Smuts argued Southwest was fundamentally a part of and entirely dependent on South Africa. Therefore, “there is no prospect of the territory ever existing as a separate state.” He expected taking over Southwest to be straightforward. He anticipated support from western European allies, and South West Africa’s whites-only Legislative Assembly had already passed a resolution in favor of incorporation. However, he soon ran into strong opposition from the UN and its Trusteeship Council as well as black Namibians.

He was unprepared for how fiercely newly independent nations and the Soviet Bloc would oppose him and he also did not count on other Commonwealth nations, namely Canada and New Zealand, to come out against him. The UN demanded South Africa place its case before the Trusteeship Council, dominated by hostile anti-colonial countries, especially India. Smuts and his advisors brainstormed ways of avoiding the Trusteeship Council but, when New Zealand placed its mandates – Samoa and Nauru – under the UN, they could hold out no longer.

Smuts and his colleagues devised a foolproof Plan B: to demonstrate that black Namibians wholeheartedly support incorporation into South Africa. Calling on the Native Commissioners for Ovamboland and Kavango, Cocky Hahn and Harold Eedes, Smuts instructed them to “sound tribes discreetly” but warned against any official referendum “unless, of course, it can be taken with safety.” As most Africans lived in the northern territories, which were ruled indirectly by government-sanctioned chiefs, Hahn and Eedes promised they would have no trouble obtaining African consent for incorporation. They just needed the approval of a handful of African leaders who were in some way indebted to the government in order to claim that the majority of black Namibians supported a merger with South Africa. Africans in the Police Zone – fewer in number, scattered across reserves, politically disorganized, and generally cooperative – would be duly consulted but were not expected to be a problem. However, Herero leaders and the residents of Berseba Reserve were not keen on incorporation.

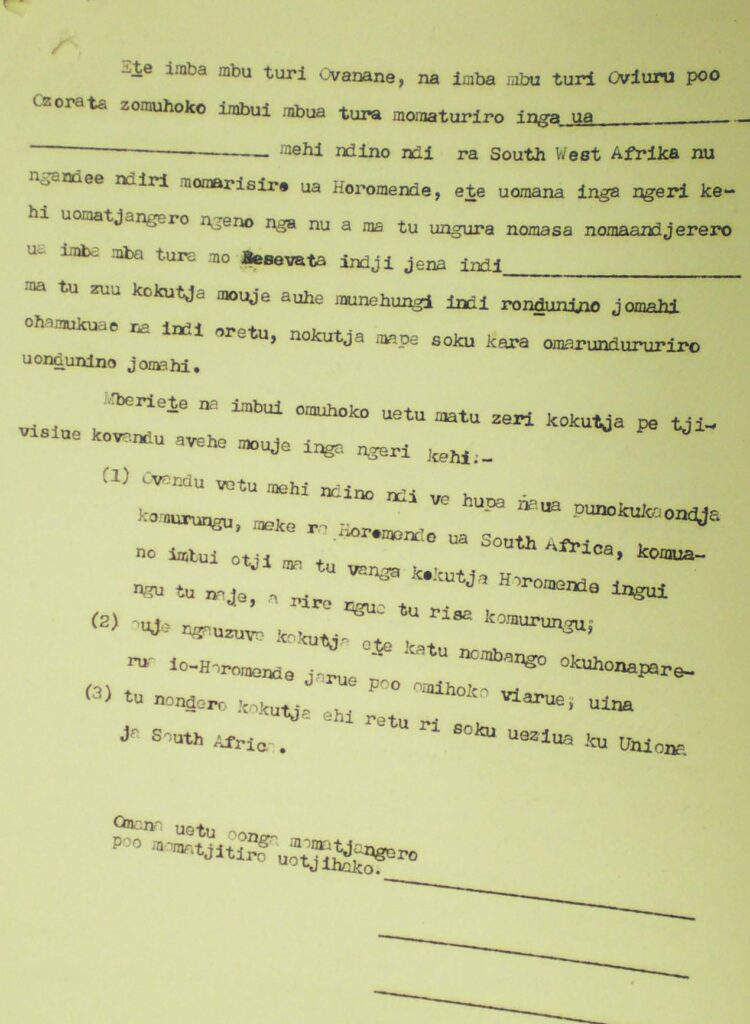

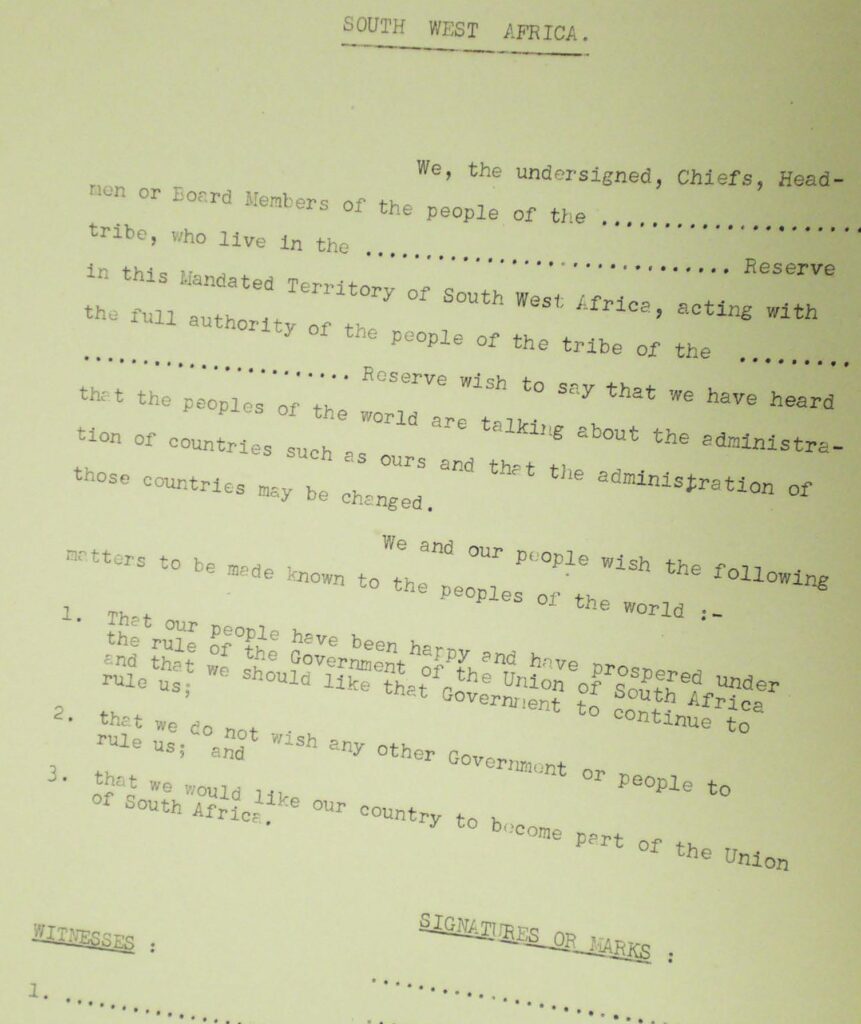

Smuts needed unanimous African consent if his plan were to have a prayer of success. He demanded the Secretary for South West Africa obtain statements from each headman in the Police Zone “unequivocally requesting complete incorporation of the territory into the Union.” Smuts even had his secretary draw up a form letter for headmen to sign! Armed with these letters, Native Commissioners dispersed across the Police Zone to deliver a speech emphasizing German colonial brutality and extolling South Africa’s virtuous rule. They were then to collect signatures on the form letters. The Trusteeship Council would most certainly have rejected these letters as proof of African support. However, Smuts first had to get Herero headmen to sign the letters, and this they refused to do.

To rectify this situation, in March 1946, the Secretary for South West Africa brought Herero leaders to Windhoek to personally convince them to agree to annexation. This meeting over Southwest’s future turned into a debate over two very different accounts of its history. The Secretary for SWA again recounted German atrocities and painted the Union’s SWA Campaign of WWI as an effort to liberate the territory’s Africans from tyranny, as opposed to a part of the British war effort and a chance for South Africa to seize its next door neighbor. Herero leaders responded by completely reframing this narrative from a story of violence to one of theft. Festus Kandjou stated quite simply, “In 1904, the Germans stole our land.” He then explained how the South African government never made good on promises to restore that land but handed it out to white settlers. Because land alienation prefaced Germany’s near-total destruction of Herero and Nama society, Kandjou’s remarks put South Africa firmly in the same category as Germany. This rallied Herero opposition to incorporation far more effectively than the government’s story of violence could sway them to support it.

A few days later, Festus Kandjou, almost certainly with the knowledge and support of Hosea Kutako, telegrammed the UN Secretary General “on behalf of the whole Herero nation,” opposing incorporation. This telegram emboldened black Namibians’ resistance to annexation, which soon turned the UN firmly against South Africa, despite Smuts’s claims that the Hereros were a mere fraction of the population and Kandjou “a native of little importance.” It compounded the already contentious issue of Southwest’s future and drove a permanent wedge between the South African government and the international community, a situation that only deteriorated after the National Party defeated Smuts in 1948. From this point on, there were only two options for South West Africa: independence and annexation. Over the next forty-five years, black Namibians, the South African government, and the international community would carry out one of the most contentious and longest decolonization struggles of the Cold War.