By: Meredith McKittrick (Georgetown University)

Originally Published 29 January 2021 [LINK TO ORIGINAL]

In February 1934, Mbambangandu wa Kare travelled from the banks of the Kavango River to Windhoek. Historical accounts offer different reasons for his presence in the city. The colonial archives state that Mbambangandu, a member of the Mbukushu royal family and a renowned rainmaker, was called to Windhoek in order to testify in the murder trial of two men whose names are given in the Supreme Court records as Kativa or Mateus Nakisha and Mukupi or N’Kopi Arranga. These men were charged with the October 1933 killing of two of Mbambangandu’s grandchildren, who had witnessed their theft of a cow. But historical accounts from Kavango indicate that Mbambangandu was brought to Windhoek against his will by colonial officials who wanted to see if he could really make rain. In these accounts, Mbambangandu unleashed the wrath of the heavens on the city, causing devastating floods and prompting colonial officials to pay him generously to cease his rainmaking activities.

These two very different stories of Mbambangandu’s trip to Windhoek represent the larger paradox of Mbambangandu’s role in the history of Kavango. He was not one of the five Kavango “chiefs” recognized by South West African colonial officials, but he had a great deal of authority. Mbambangandu had inherited the famed rain charm from his uncle, Mukoya, in 1921. Over the course of the next decade, he moved with a large number of followers from Angola to Botswana to Namibia. He finally settled in the Gciriku kingdom, not far from the officially recognized fumu and rival rainmaker, Andara.

Mbambangandu’s arrival coincided with a severe, years-long drought that affected much of southern Africa. By 1930, Kavango chiefs were reporting that some of their subjects were dying of starvation. The drought peaked in 1933 and Mbambangandu was called upon by his neighbours to intervene. The Native Commissioner, Harold Eedes, reported that local rulers sent cattle to Mbambangandu, but it did not rain.

Historian Maria Fisch, citing now-missing missionary records, states that Mbambangandu sacrificed one or two new-born children in rainmaking ceremonies held on the Angolan side of the border at this time. The sacrifice of royal children was a reported part of Mbukushu rainmaking ceremonies. Eedes was aware of these rumours, but in his June 1934 report he wrote that Mbambangandu had “stopped his evil practices, such as child sacrifices.”

These comments on human sacrifice, the persistence of a deadly drought, and the disappearance of Mbambangandu’s grandchildren certainly raise questions about the nature of the crime that was being tried in Windhoek. The men – and, indeed, everyone who was interviewed in the case – seemed a lot more interested in the death of the cow than in the death of Mbambangandu’s grandchildren, raising the possibility that they had in fact been sacrificed in a rainmaking ceremony and that everyone knew it.

Kativa and Mukupi’s opinion on what crimes had really been committed come through in the extensive courtroom testimony—in language that is stilted and awkward in translation, yet forceful. Kativa insisted that they had killed the cow because Mbambangandu had not fed them. ‘Our guilt is not so great; the guilt is with Mbambangandu, he did not give us any food for the road.’ Kativa and Mukupi talked so much about the cow that the judge instructed the court interpreter: ‘Make it clear to them the whole trouble is not about the cattle slaughter, but it is about killing the children.’ On that subject, the two men insisted that they had killed the cow but that ‘we didn’t see the children.’ The court did not question this blatant contradiction to the men’s own recorded confessions.

Those confessions had not been given freely. The accused men, who were brothers, had been tortured on Mbambangandu’s orders before they admitted to killing the children; one of them had visible injuries four months later. And they painted for the court a vivid picture of an unequal and coercive relationship. Mbambangandu had accused their brother of witchcraft, seizing all of his property, and driving him out of the community. This, the men said, was how they had become impoverished to the point of starvation. They also hinted that their status as Mbambangandu’s dependents was not entirely voluntary. The word ‘slave’ never appears in the court records, but testimony was translated across four languages and many nuances are lost. Certainly, Mukupi and Kativa do not seem to have been entirely free men. They had no parents or other relatives in the region, they had no independent access to land or cattle, and Mbambangandu had commanded that they live in his house.

Neither Native Commissioner Eedes nor the court had any interest in exploring the nature of the violent relationship between Mbambangandu and the two men accused of murder. Instead, Eedes insisted that Mbambangandu did not have any real power over people along the Kavango River. And the judge in the trial claimed that once the two men were ‘handed over to European authorities,’ any fear they had of Mbambangandu would have evaporated. ‘It must have been obvious to the accused that they could now snap their fingers at their tribal authorities,’ he told the courtroom. This self-congratulatory attitude toward colonial beneficence was the justification for upholding the men’s earlier confessions, which they had repeated to a colonial magistrate. The court sentenced the men to death by hanging – a sentence that was commuted to twenty years’ imprisonment with hard labour.

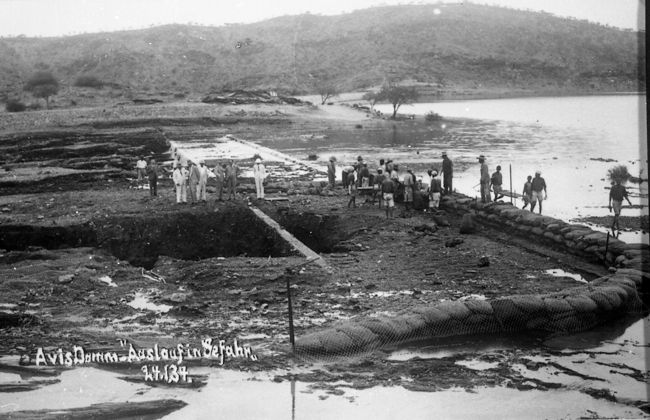

With that, Mbambangandu returned home, and Kativa and Mukupi vanish from the written record. Heavy rain continued to fall around South West Africa, washing out roads, bridges, and railway lines. The South African air force investigated ‘a mysterious lake’ that had appeared in the Kalahari, where the Nossob and Molopo rivers had flooded. In western Ovamboland, 1934 became known as the year of Shiwenge, for an Angolan rainmaker credited with breaking the drought. Fisch, citing missionary sources, says Mbambangandu was evicted from the Kavango in 1940 for practicing human sacrifice, and died near the Luyana River a few years later.