By: Dino Estevao & Lennart Bolliger

Originally Published 11 December 2020 [LINK TO ORIGINAL]

Forty years ago, in April 1980, my hometown of Chiede in southern Angola was attacked by the 32 ‘Buffalo’ Battalion of the apartheid-era South African Defence Force (SADF). I was only nine years old. What followed was a gruesome massacre of at least 76 civilians – men, women, and children. Like many other events which took place in what became known ‘Border War’ and have remained untold, the attack left my family and countless others torn apart and haunted by the scars of war. To this day, many former members of the SADF, however, vehemently deny that any such massacres took place.

The attack on Chiede was not an isolated incident. Starting in 1975, the people in southern Angola were under near constant harassment by low flying SADF fighter planes that were surveying the area. Most feared, however, were the SADF helicopters that would drop off soldiers and pick them up after they had swept through the homesteads looking for SWAPO guerrillas. The SADF was not only terrorising the population but brought the local administrative system, including schools and hospitals, to a grinding halt. People only moved in small groups that were big enough for self-defence against opportunist armed bandits but small enough not to attract the attention of the SADF’s air force that might mistake them for guerrillas. Life in Angola became unbearable as people could no longer work in their fields or herd their livestock.

Chiede was linked to the provincial capital of Ondjiva by a road which crawled through the administrative capital of Namacunde. The road between Chiede and Namacunde was about 25 kilometres long and was used by the provincial government to supply food and necessities to Chiede and beyond toward the more remote areas along the border. As a result of bombardments, ambushes, and landmines, this stretch of the road became a death trap with only few brave or desperate souls venturing through. The local population at Chiede was becoming ever more trapped and isolated.

After the SADF withdrew from Chiede in April 1980, the local population identified at least 76 bodies that had been left scattered in the fields. Many more people were displaced or left homeless. Most of the people who were killed were women and children, who sought refuge in the north-eastern part of town as the SADF approached from the southwestern side, isolating Chiede from Namacunde and Ondjiva. As I would find out only 15 years later, among the bodies found was that of my older brother, Leo, who had only been 12 years old. Those whose bodies were not found were declared missing – I was one of them.

During the attack, I had been with four other people in one of the homesteads: an elderly man, two women who were sisters, and a six-year-old girl. The young girl, who managed to escape, was the first to notice that I had been shot in both legs. Shortly afterwards, I was lying on the ground with soldiers pointing their guns at me and witnessed how the two women right next to me were executed. Suddenly, seemingly out of nowhere, a soldier came running and shouted, ‘Don’t kill the boy!’ I was told to stand up and walk towards the water pump nearby where I was put in a helicopter together with the elderly man who was blindfolded and had his hands tied behind his back. We were flown to Oshakati where I was taken to the military hospital and the man become a prisoner. (He was later released as part of a prisoner exchange programme.)

Since I was the youngest patient at the hospital, both the hospital staff and other patients took an interest in my wellbeing. Some patients were 32 Battalion soldiers helped me because, like them, I was from Angola and spoke Portuguese (as well as Kwanyama). The other patients were Oshiwambo-speaking soldiers from other SADF units in Namibia and also tried to help me. Before I was discharged from the hospital, there was a lot of discussion whether I should be sent back to Chiede but that option seemed too dangerous. Some of the men at the hospital knew what had happened there and also advised against it. In a cruel twist of fate, it was decided that I should be sent to the Western Caprivi to live at the base of 32 Battalion and be adopted by one of the families there!

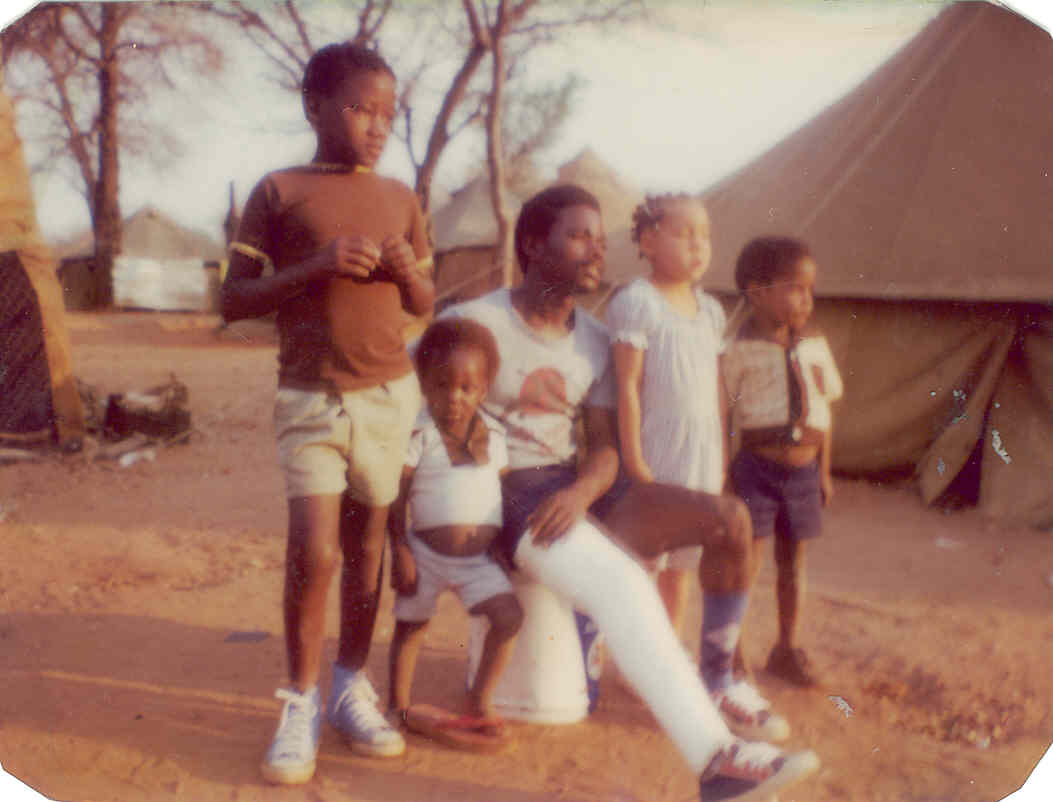

I arrived at the so-called ‘Buffalo’ base in early September 1980 and met my adoptive family for the first time at the ‘Kimbo’, the civilian section of the base. The latter included a shop for the soldiers and their dependants, churches, and a school that I immediately started to attend. However, after two years, my adoptive family was expelled from Buffalo. I was then moved to the ‘orphanage’, a bungalow where other orphaned boys lived. For the next ten years, I lived as an orphan in 32 Battalion’s military community, and many of my friends were also either war orphans or children being raised by single parents or distant relatives.

On the eve of Namibia’s independence in 1989, the SADF began to withdraw from Namibia and the Angolan community at Buffalo (like its counterpart of 31/201 ‘Bushman’ Battalion at the Omega base) was moved to South Africa, more specifically Pomfret, an abandoned asbestos mining town. After matriculating in 1992, I decided to leave Pomfret and settled in Potchefstroom in search of a job and better opportunities.

Both while I was in Namibia and later in South Africa, I tried to get in contact with my family back in Angola but with no success. I wrote letters through the International Committee of the Red Cross and sent other messages through people who knew others who were crossing the border into Angola under very high risks. I never heard back and did not even know if any of my letters or messages ever arrived. However, in 1995, I finally had a breakthrough….

Continued in Part Two: [LINK]