By: Pekka Peltola (Independent Scholar, Finland)

Originally Published 28 April 2017 [LINK TO ORIGINAL]

In 1995, I completed my doctoral thesis, titled The Lost May Day: Namibian Workers Struggle for Independence. In this text, I sought to show that the affiliation of the National Union of Namibian Workers (NUNW) with SWAPO, while perhaps assisting with the transition of Namibia to independence, could be a mixed-bag in the post-independence period. Delegating to SWAPO leadership the power to define workers’ interests could easily cause conflicts between workers and the post-independence government, especially where these interest groups face cleavages. I tried to argue, based on the experience of post-socialist states in Europe, that allowing the ruling party to run trade unions and dictate their agendas could lead to the end of organised labour or society in general – a major loss to Namibian workers.

While I was working on this doctoral thesis in the early 1990s, I spoke with Andimba Toivo ya Toivo about these issues. In my July 1992 interview with him, he put the problem simply: “Once the trade unions are also down maybe when the elections come one day they will just say: ‘Ah, what is the point? This government of ours is not helping us, I am not going to vote.’ Then where are we going to end up? So, it needs really a lot of training and educating our people to understand.”

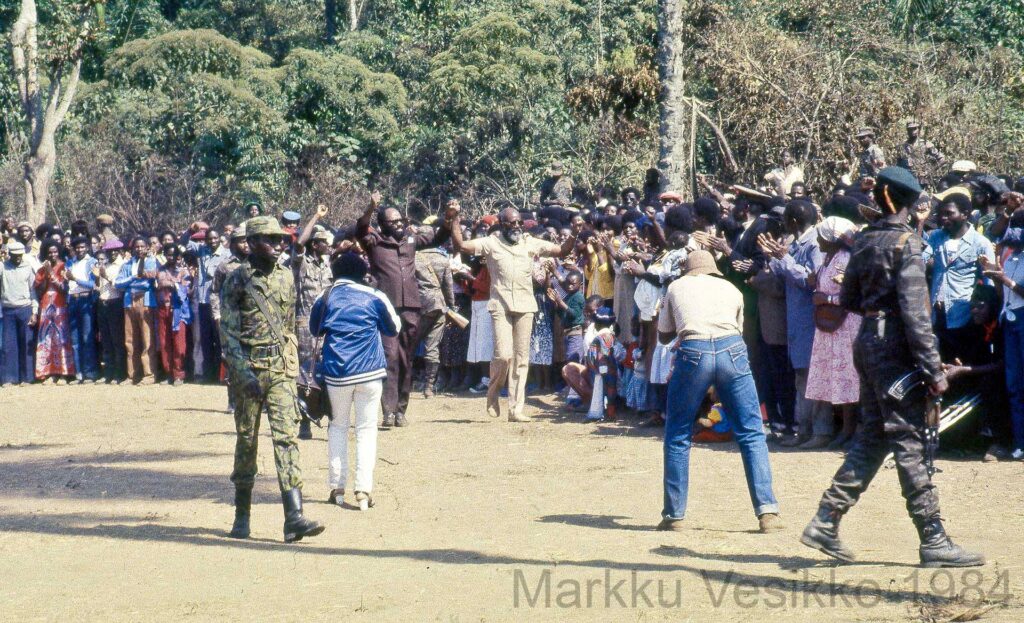

Photo by Pekka Peltola

We see now, that the great Andimba Toivo ya Toivo understood Namibian workers better than I did. The result of worker’s disappointments with SWAPO-led NUNW have led to several crises, but it has not led to a collapse of trade unions or the society. Affiliation with political parties always spreads its divisions and internal struggles inside unions, badly diminishing their unity and credibility. Some ousted leaders of NUNW have established competing organisations. Still, despite several purges of trade union leaders and their replacement with those loyal to SWAPO leaders, NUNW has retained a measure of healthy support.

Cooperation with Namibian government structures has produced vast improvements in labour legislation and real minimum wages have increased considerably during independence. If we compare the Namibian case to Botswana, a nation with similar size and dependence on mining, we can see that Namibian workers earn more and have more to say in governance than workers in Botswana. Still, the reduction in voter turnout in Namibia is a fact. Slow participation in grass roots work in Namibian unions seriously weakens them. Unions have in some ways become stepping stones to high positions in the government and, alarmingly, in business, where trade union leaders have accepted invitations to become directors creating serious conflicts of interest. One example is Petrus Nevonga of the Namibia Public Workers Union (NAPWU), who took a strong role in failed investment policies of GIPF, the pension fund for public sector workers. Nevonga was fired but later reinstated in his union.

According to union statistics, almost half of formally employed Namibian workers are organised in trade unions. Although the real figure is considerably less, this is more than anywhere in Africa, even beating South Africa, which has a strong tradition of unionisation. A good organising rate is not only due to NUNW efforts, but also to the existence of important rival organisations. The status of public sector unions attached to the government is helpful for ensuring that both sides of the negotiation table understand the importance of independent unions. The Trade Union Congress of Namibia (TUCNA) gathers workers, who share the necessity of workers independence from employers and government. On the other hand, unions loyal to SWAPO, like NAPWU, have sailed from internal conflict to another and caused purges inside NUNW as well.

SWAPO has always had a very negative view of strikes; perhaps they want to have them forbidden, but they have not dared to act on this. This attitude has made it quite difficult for NUNW to accept education and training from more experienced COSATU of South Africa. COSATU understands that striking (workers withholding their labour) is at the end of the day the only real muscle the workers have. Therefore, wherever organisation of labour is allowed, there must be strikes – legal or illegal. This could be seen in the Ramatex-strike in 2006 in Windhoek. 90% of the workers voted for striking, which was vehemently opposed by SWAPO and the union leaders. Workers won the strike easily.

Knowledge and practices of the South African trade union experience came to Namibia in 1996 with the arrival of Herbert Jauch. With some support from Finnish (SASK) and Dutch trade unions he established the badly needed Labour Resource and Research Institute (LaRRI), which was independent from, but close to the NUNW. The ably led training and research of LaRRI provides unions with a constant flow of educated cadres capable of working on the grass roots level. LaRRI has also been important in developing cooperation of workers’ organisations all over Africa. Sharing information, strategies and creating international support has always been a central element in the work of successful unions around the world.

Therefore, Namibia has not followed the path of former socialist countries of Eastern Europe, where the extreme domination of the ruling party made trade unions impotent and permanently void of all credibility. To an extent, Namibian trade unions might be able to lend support to workers in Botswana, who still have a long way to become an effective force able to support its members.