By: Ariane Komeda (University of Bern)

Originally Published 26 May 2017 [LINK TO ORIGINAL]

Brick, Stone, Corrugated Iron. When the German colonists came to Namibia, their choice of building materials were simple, and without great variety. In previous generations, Germany had its own tradition of building with strategies like clay construction, but as the industrial age gained momentum, European town planners gave up these time-proven traditions and sustainable building methods. Colonial architects and German settlers soon followed, and in order to appear “modern”, they brought with them to Namibia materials reflecting their industrial heritage in Europe. Steel, cement, and other materials required the input of fossil fuels, oils, and coal to make their building strategies possible

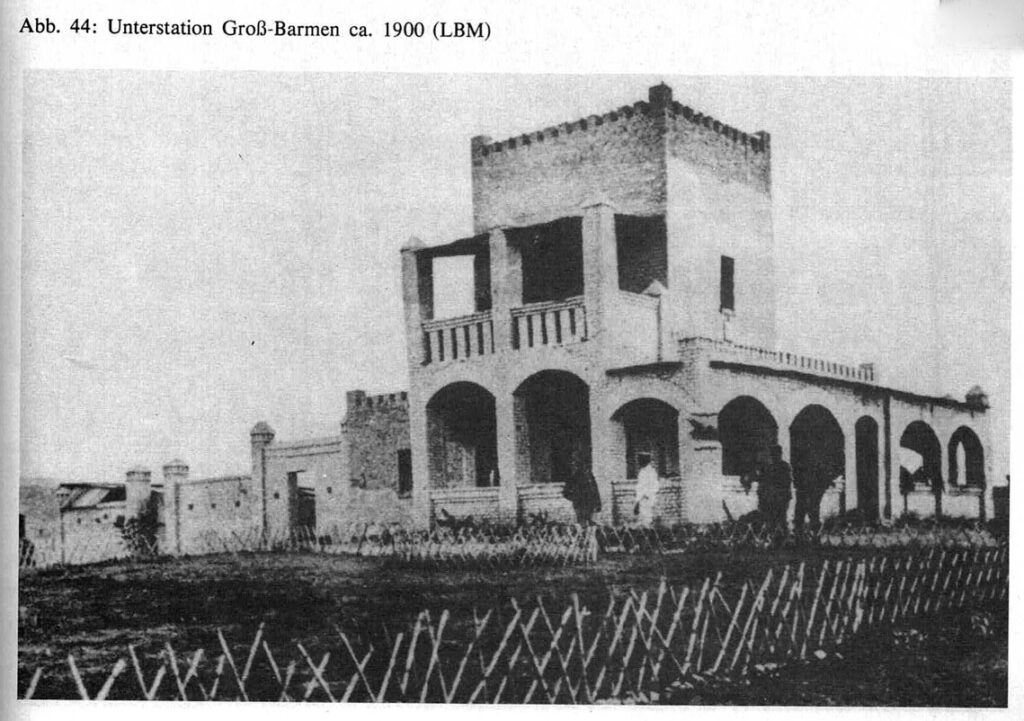

When we look at the history of architecture, it becomes clear that after war or military intervention, building strategies and architectural forms follow as an expression of colonial expansion. Erecting buildings in specific ways symbolised an important part of colonial consolidation, of possible legitimation, and perhaps most importantly, cultural distinction. Even if it was expensive and impractical, it was deemed that a German colonial house had to be square, solid, and most of all, unlike African housing. Very few German colonial builders chose to test the available range of natural materials in Namibia. The average settler, however, was conflicted between the official guidelines given by the German state and the local knowledge presented by African rulers and cultural intermediaries. In the end, climate, culture, resources, and inventiveness were the main drivers of colonial housing in Namibia.

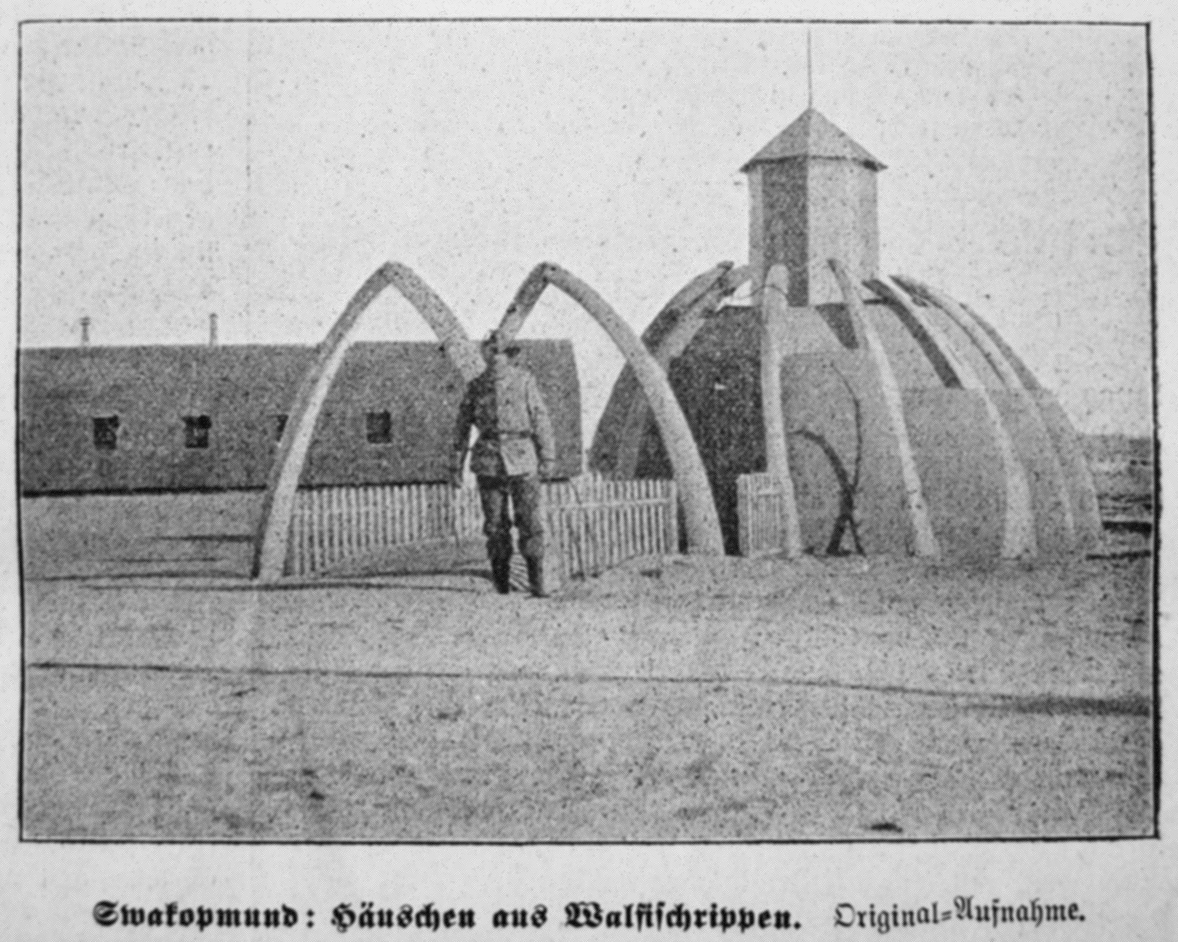

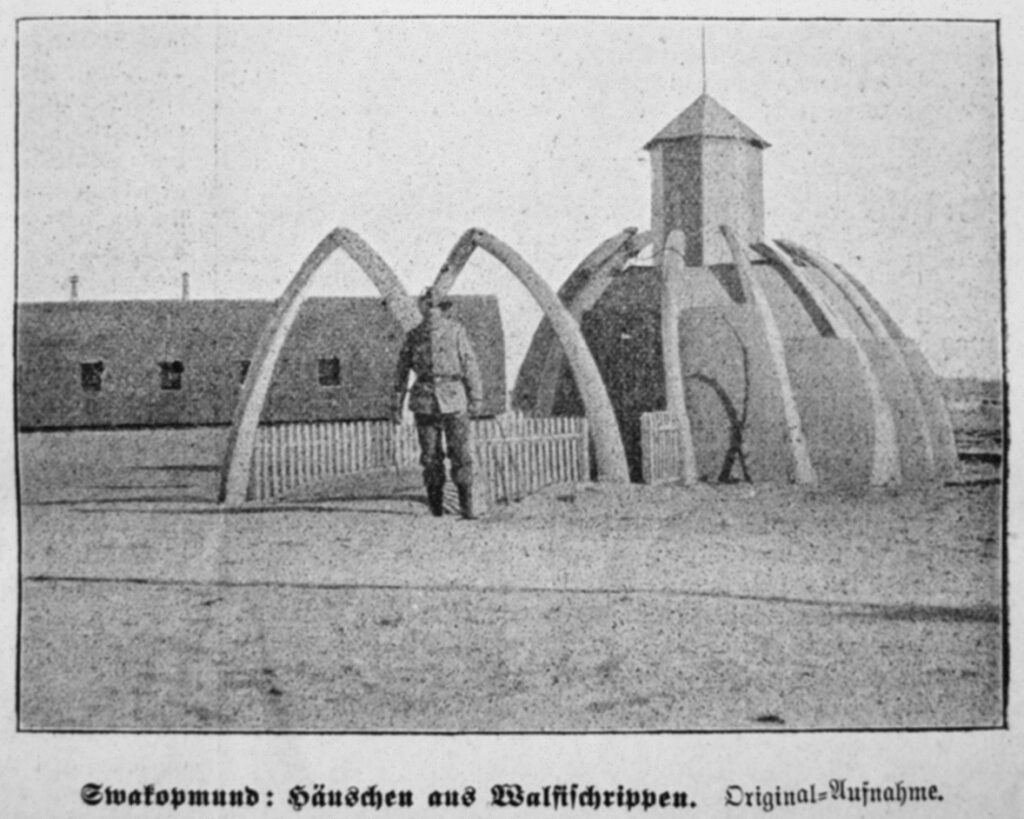

Germans shared a number of architectural keywords with their African counterparts, such as open structure, ventilation, and the dominant roof. However, the African people in Namibia were far more flexible in their methods, utilising sunburnt clay, dung, wood or wheatgrass in accordance with traditional designs. Simple logistics and a high degree of mobility as a result of lightweight materials meant that their architectural traditions were maintained through notions of minimal waste. This wasn’t the aim of most of the European settlers, though.

The German colonists, on the other hand, were driven by the material they used, building the walls in a rectangular shape. At the same time, they were fascinated by the new attributes of industrialisation, such as mass production and dense transportation networks. In order to justify modern industrial achievements, the colonists tried to form abstract building norms and methods. Banning organic substances from housing, claiming it was inferior materials, was part of this dazzling illusion of “advanced civilisation”.

For example, materials like metal and rubber isolators such as tarboard, as well as European construction principles like solidity were neither physically nor climatically grounded in the Namibian situation, and therefore they were not particularly suitable for the colony. Similarly, wherever it came to the question of positioning a farmhouse or a settlement, European concepts mostly failed. Building a house near water or a group of trees was acceptable in colder climates, but after only a few years in Namibia, this practice turned out to be inconvenient as it could lead to malaria transfer in the wetter areas. The transfer of German ideas and concepts about architecture and planning to Namibia implied a housing which was more representative than practical. One purpose of building this way was to emphasise cultural distinction and ideas about “civilisation”. However, this technical optimism was constantly put under pressure, and it was often replaced by the more convenient implementation of specific African building practices.

Even more significant than building materials were the range of ideas about more practical construction in Namibia. Local “traditional knowledge” was often collected and treasured by some of the European missionaries, who were themselves very respected among both the African population and the Germans. Furthermore, there were “cultural brokers” among them who had little interest in supporting imperialism or European architectural strategies.

Some of the observations of these “cultural translators” were carefully transferred into metropolitan language and brought back to Berlin. There, this knowledge entered into publications, ethnographic exhibitions, and also international architectural and design competitions. This doesn’t mean, however, that this knowledge was always accepted. Corrugated iron roofing, for example, continued to be cultivated in various parts of Africa, but it was in fact expelled from an architectural competition for a government building. This was mentioned in a supplement to the Deutsche-Kolonialzeitung in March 1914.

To sum up, in the German days, the search for a suitable colonial architecture was a complicated process, intertwined with the European ideals of industrial production, alternative European movements, and practical African building methods. Eclectic choices represented an array of styles. This resulted, for instance, in the increasing numbers of verandas built in Windhoek and elsewhere. For many reasons the veranda can be seen as a fusion of African, Asian and European elements, presenting a zone of contact and intercultural communication. Verandas more than any other element made it possible to fuse such packed transcultural moments into architecture with its own identity.