By: Brooks Marmon (University of Pretoria)

Originally Published 26 January 2018 [LINK TO ORIGINAL]

As Zimbabwe enters a new political dispensation following the resignation of Robert Mugabe, the country’s relations with Namibia remain strong. Both of Namibia’s former Presidents, Sam Nujoma and Hifikepunye Pohamba, attended the inauguration of the new Zimbabwean leader, Emmerson Mnangagwa. On a state visit to Zimbabwe last April, Geingob praised then Vice–President Mnangagwa for his role in helping SWAPO prepare for the 1989 elections.

The historic ties between the two nations are likely most evident to the contemporary Zimbabwean observer as s/he strolls down a major thoroughfare in Harare’s Central Business District bearing the name of Sam Nujoma.

However, the high-ranking diplomatic delegations of the present were preceded by much more grassroots friendly missions during the liberation struggle. In June 1981, newly independent Zimbabwe hosted a ‘Namibia Solidarity Week’, consisting of a series of mass rallies followed by private evening cocktail parties featuring SWAPO cadres. Both of Namibia’s former Presidents participated in the event, which marked Nujoma’s first visit to the country since the independence celebrations of April 1980.

Zimbabwean Foreign Minister Witness Mangwende stated that the Week was “in line with the plans formulated by the Frontline States…to show their support for SWAPO as the sole authentic representative of the people of the Namibia.”

The Zimbabwean government exerted maximum effort to ensure that the event was a success, scoring not only a morale boost for SWAPO, but also strengthening its own domestic support base and international bonafides in the process.

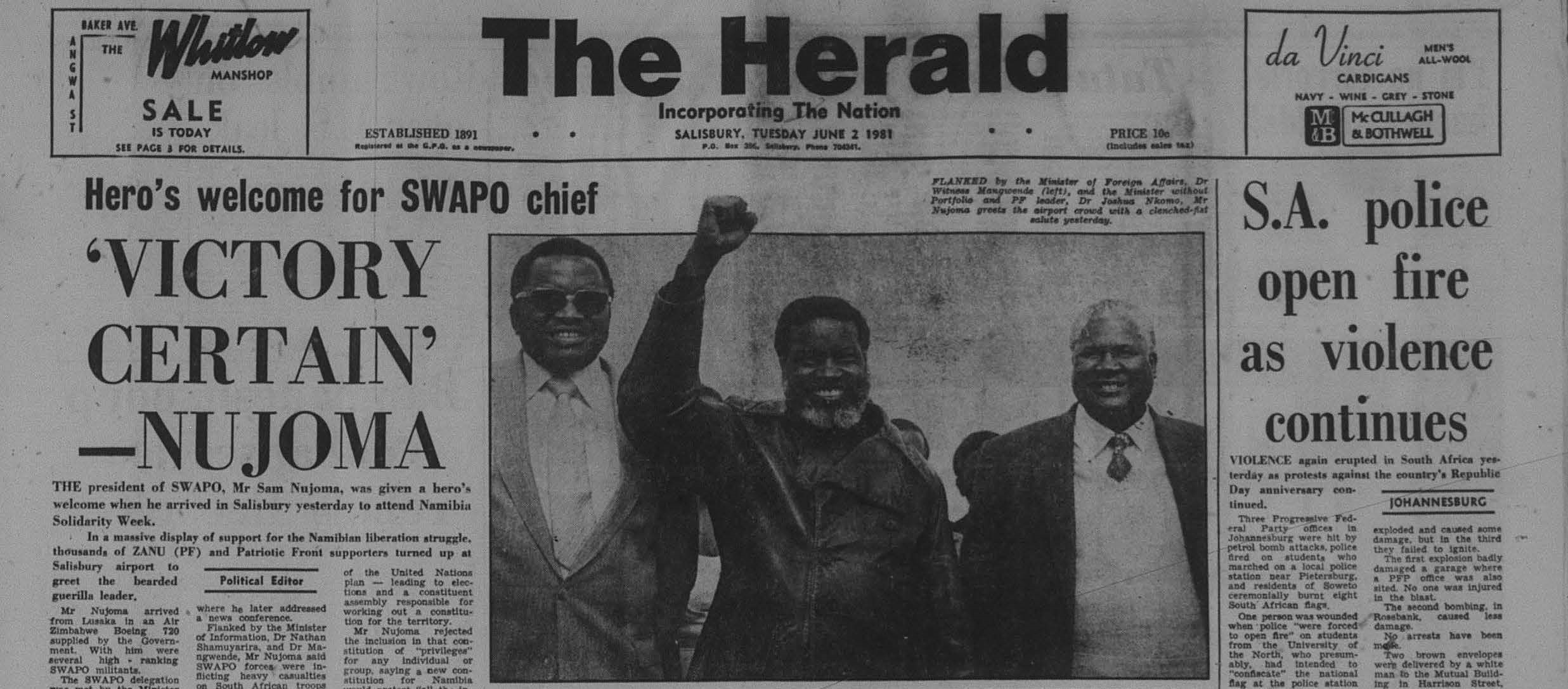

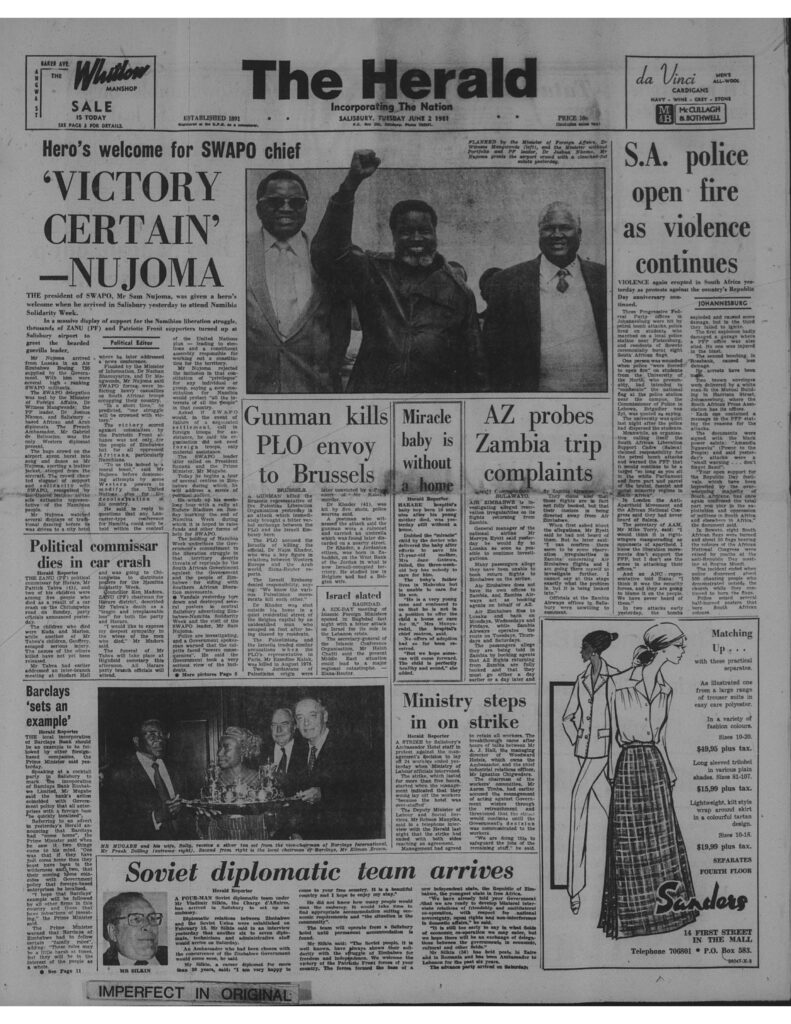

The Herald, Zimbabwe’s state newspaper, gave SWAPO and the Namibian liberation struggle front page coverage throughout the Week. An op–ed proclaimed that Zimbabwe was demonstrating “that it was prepared to go all the way with SWAPO in the armed struggle against the racists.” The streets of central Salisbury (as the capital was then known) and surrounding townships were also plastered with posters announcing the solidarity week.

The SWAPO delegation arrived in the capital, to be renamed Harare the following year, on June 1st via Lusaka on a plane provided by the Zimbabwean government. They were met by thousands of adoring supporters from the Zimbabwean public, prominent politicians, such as ‘Father Zimbabwe’, founding nationalist leader Joshua Nkomo, and a number of local diplomats.

Following displays of traditional dance, Nujoma visited Zimbabwe’s Heroes’ Acre, final resting place of a number of stalwarts of the liberation struggle. He then held a press conference in the city centre, flanked by Zimbabwe’s Ministers of Information and Foreign Affairs. He predicted that the military struggle would be won “in a short time”, condemned the role of Western powers in derailing United Nations plans for Namibian decolonisation, and stated that no ethnic groups should enjoy special privileges under a democratic Namibian constitution.

For the remainder of the week, the Namibian contingent held mass rallies across a broad swathe of the country, joined by a rotating cast of prominent local political figures. The themes were generally the same as those outlined in the initial press conference and broadly similar to those that the Zimbabwean government has pushed over the last two decades – condemnation of the subversive tactics of the West (particularly the young Reagan administration in the US) and a celebration of violent resistance against reactionary imperialist forces.

The first mass rally was held in the second city of Bulawayo, at the Barbourfields Stadium, in a township of the same name. The delegation, which in addition to the two future presidents included Kapuka Nauyala (future head of SWAPO’s Harare office) and Women’s Council leader Pendukeni Kaulinge, then headed north, holding three rallies at various rural centres in Mashonaland Central Province the following day. They were joined by an array of local dignitaries, including Victoria Chitepo (widow of prominent assassinated ZANU leader, Herbert Chitepo) and Joice Mujuru, future Vice–President.

State media reported that the rural Zimbabweans ‘showered’ the SWAPO emissaries with gifts, including livestock, cash, and Nujoma’s favourite, a walking stick with a concealed knife. Government encouraged further offerings from across the country and established a donation point on the first street pedestrian mall in the heart of the Salisbury city centre, with Joice Mujuru, Minister of Community Development and Women’s Affairs leading the collection drive.

From Bindura in Mashonaland Central, the Solidarity Week returned to Zimbabwe’s urban centres, visiting the third and fourth largest cities, Mutare and Gweru, which were then still known by their colonial names, Umtali and Gwelo, respectively. Both rallies attracted major government figures. In Gweru, the SWAPO dignitaries were joined by Minister of Youth and Sport Ernest Kadungure and Deputy Foreign Minister Simbarashe Mumbengegwi, a member of Mnangagwa’s new cabinet who remains an influential figure. At the penultimate rally in Gweru, Nujoma was flanked by ZANU – PF Secretary, Edgar Tekere, one of Mugabe’s most radical lieutenants.

The final and largest rally took place at Rufaro Stadium, site of the independence ceremonies the previous year in Harare’s historic Mbare township. It was the only rally in which Prime Minister Mugabe joined Nujoma.

Mugabe gave a substantial and confrontational address. Stating that the Solidarity Week had ‘perturbed’ the Apartheid state, he proclaimed that Zimbabwe “will fight [S.A. Prime Minister] Botha’s regime if it dares to attack us.” With echoes of Kwame Nkrumah, Mugabe declared that “our own victory in Zimbabwe can only have full meaning and significance if Namibia and South Africa are freed.”

Namibia Solidarity Week provided a boost to both SWAPO and the young government of Zimbabwe. Nujoma raised the issue of a SWAPO office in Harare, which would soon be established and also initiated a dialogue on the admission of Namibian students to the University of Zimbabwe.

However, it was probably the Zimbabweans who gained the most from the week’s events. A large number of local political figures shared the stage with Nujoma, delivering populist discourse and situating Zimbabwe’s actions within the framework of the Frontline States and the Organization of African Unity. Just days after the SWAPO leaders departed, a high-ranking delegation from the US State Department visited Harare to discuss the political situation in Namibia.

In hosting the solidarity week, Mugabe’s government took a key step to elevate its international status as a crucial player in the final liberation of the continent, a contribution crowned by Zimbabwe’s chairmanship of the Non–Aligned Movement on the eve of Namibian independence.

With the resignation of Robert Mugabe, it is widely expected that the Mnangagwa administration will renew outreach to the West. The weight of history and a deep legacy of militant oratory, evident in Zimbabwe not only during the liberation struggle and in the aftermath of sanctions and land reform, but also in between, may complicate efforts to adopt a new tone.

Regardless, the post-independence trajectory of each country offers valuable lessons for the other.