By: William Blakemore Lyon (Humboldt University of Berlin)

Originally Published 2 March 2018 [LINK TO ORIGINAL]

Once the colonial war against the Herero and Nama began in 1904, the German occupiers of Namibia found themselves in an acute labour shortage, especially once the war morphed into genocide. Many of the African inhabitants of the ‘police zone’ were either killed or forced into hiding or exile, and the German administrators then did not have enough readily available local workers to build new railway lines. At the same time, trains were becoming necessary to supply and transport the growing German army throughout the colony.

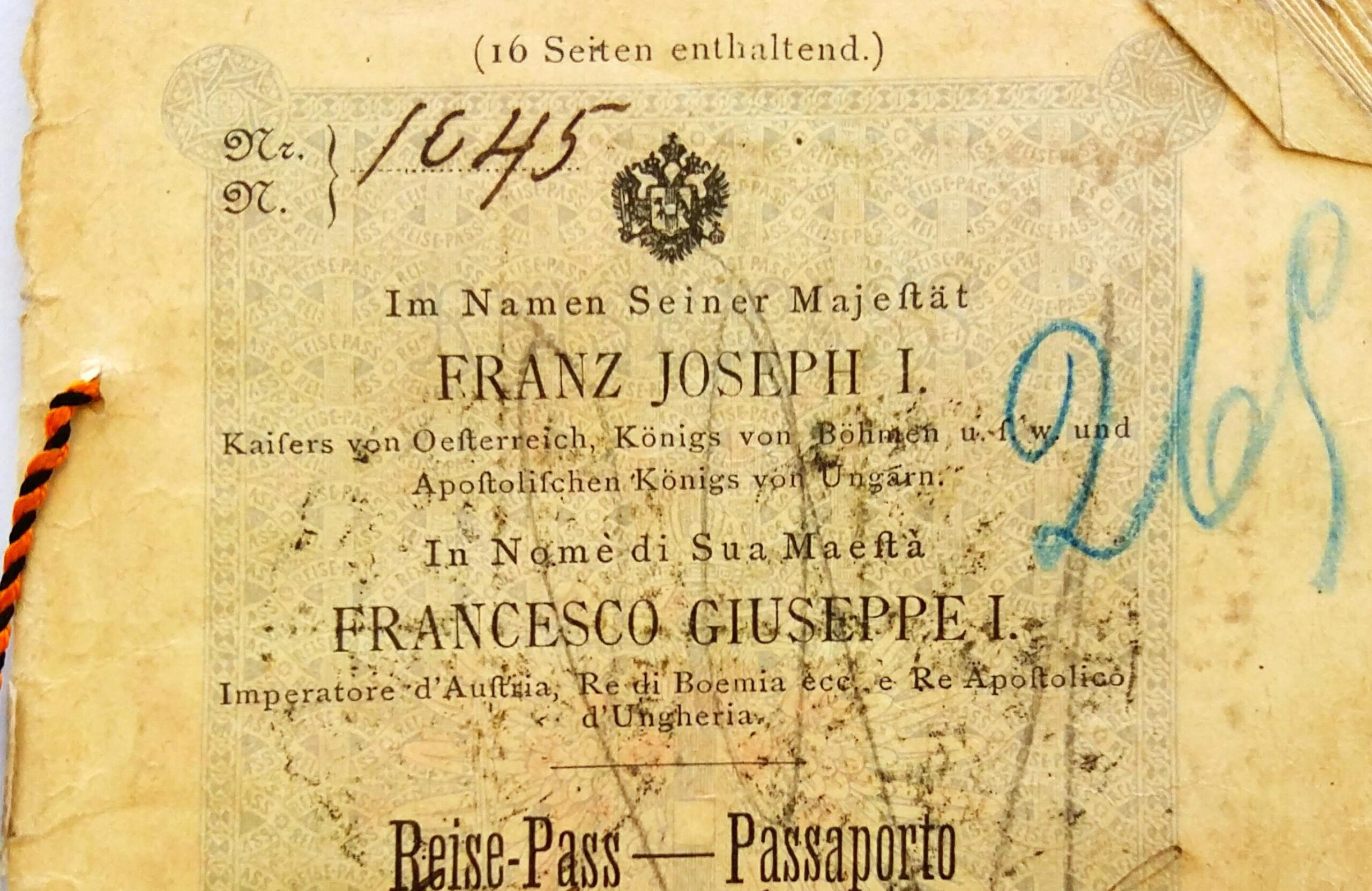

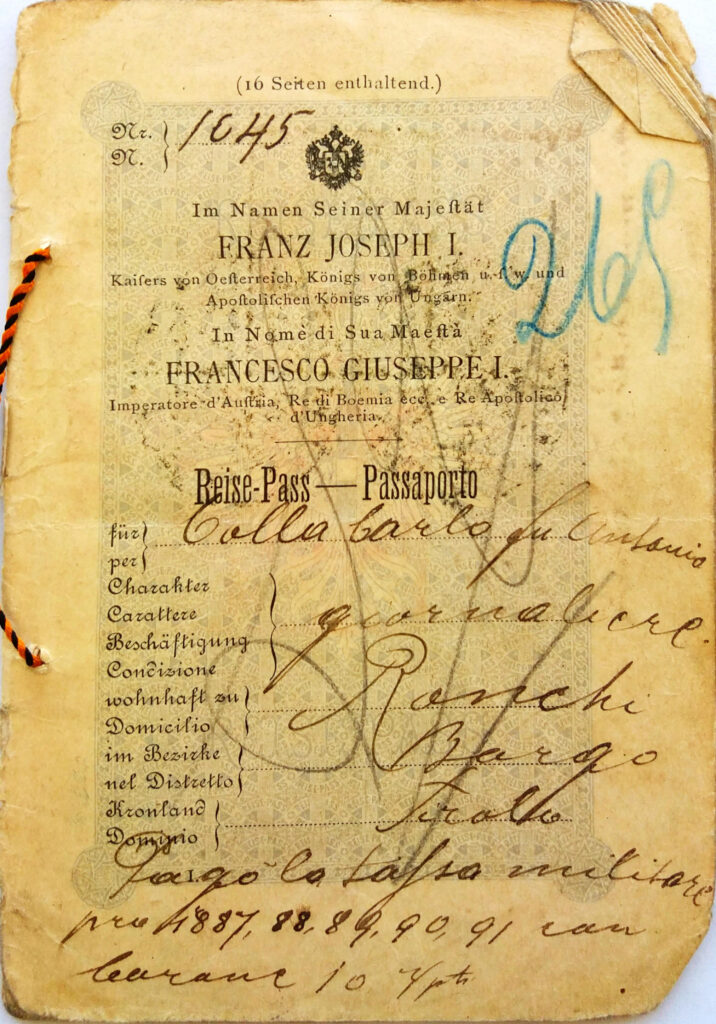

While it is quite well known that they eventually utilised Nama and Herero forced labour from their concentration camps, their early solution was to import labour from abroad. In 1904, the Berlin firm Arthur Koppel & Co hired around 300 workers from Europe to staff the railway-building gangs. These individuals were Italian speakers, and while most came from Italy, others came from Switzerland and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. All were recruited by Mr. Luigi Zarossi who had opened an office in Swakopmund by 1904.

The workers came from diverse European cities such as Milan, Venice, Perugia, Torino, Geneva, Rome, Bergamo, and Trento. They worked throughout the colonial railway system at most of the important stations: Rössing, Welwitsch, Pforte, Swakopmund, Khan, Wilhemstal, Karibib, Windhoek, OKasise, Waldau, Okahandja, Teufelsbach, Brakwater, Pforte, Jakkalswater, Friedrichsfelde.

However, upon beginning their contracts in 1904, many of these labourers found that working conditions and pay were not what they expected based on their initial contracts. While the workers had believed their accommodation would be in houses, they were instead given tents and made to sleep on the ground. Additionally, they were only provided with distilled ocean water to drink, which reports from the period indicate was often barely fit for human consumption. Lastly, they were not paid their promised salary.

The combination of these difficulties led to many workers going on strike which in turn caused considerable problems for the timely completion of railway work in the early phases of the war, specifically to Karibib and Omaruru. Some of these protesting workers decided to return to Europe, however, their employer refused to pay for their promised return tickets home. Arthur Koppel & Co argued that because some workers left without having finished their contracts, they were not obligated to pay for their return tickets.

Aggravating the workers further was the fact that they were not allowed purchase tickets to the Canary Islands: the easiest and most cost-effective place to obtain transport to Italy. Workers instead were forced to purchase tickets to Hamburg, most likely in a blatant attempt to ensure that the money on the tickets was spent on German rather than foreign transport companies. From Hamburg they would then need to travel south through most of Germany to get home. The scale of these original workers’ difficulties led to debate in the German Reichstag over the story’s negative coverage in the Italian press. August Babel of the Social Democratic Party argued that this debacle was a major problem for Germany’s image as their nation was supposed to be one of social reform.

While debate continued in Berlin and some of the initial Italian workers left, many others stayed, and more were eventually recruited to the colony in the following years. The total number of Italian-speaking workers employed by German companies and the colonial government prior to the First World War was in the range of 1000-2000 individuals. However, most of the workers had departed Namibia before the South African military installed martial law, and more were repatriated to Europe in the early 1920s by the new colonial administration.

The story of these Italian speaking workers, who have received almost no scholarly attention, is part of my doctoral research at Humboldt University in Berlin. The project is a comparative social history of various groups of migrant workers who laboured in Central and Southern Namibia between the years 1890 and 1925. This project documents the lives of not only these Italian migrants who made up a relatively small percentage of the total number of workers, but also individuals from the northern Ovambo kingdoms, as well as those from the Cape, Liberia, Togo, Ghana and Cameroon. Most came to Namibia’s ‘police zone’ to work in the mines, on the railways, or as longshoreman at the harbours. While much scholarly attention has been focused on the Ovambo workers, especially during the South African colonial period, little work has concentrated on the various other groups included in this study. Furthermore, no research has compared their experiences or examined how they interacted with one another.