By: Lachlan MacNamee (Stanford University)

Originally Published 17 February 2017 [LINK TO ORIGINAL]

Much of Namibian politics turns on the issue of ‘tribalism’ – the common term in Namibia for when someone makes a political argument based on ethnicity. For example, early last November, former deputy minister of land reform Bernadus Swartbooi caused quite a stir. Passionately arguing against the resettlement of individuals from the north into ǁKaras Region, Swartbooi implored Namas, Hereros and Damaras to “stand up” and defend their land. Expectedly, President Geingob later sacked Swartbooi. Yet, judging from the widespread reaction caused by Swartbooi’s remarks, it’s obvious that many believe that he has a point.

Should land reform in Namibia be ethnically blind – targeted at the poorest Namibians, regardless of ethnic identity? This would naturally mean that most redistributed land will tend to go to people from the densely populated north. Or should land reform by done in a way that respects the historical claim of particular ethnic groups to traditional lands? Swartbooi’s comments are an example of a much wider and thornier issue – what role should ethnic claims play in Namibian politics?

This question has divided Namibians since independence. SWAPO rose to power under the unifying platform of “One Namibia, One Nation” in 1990 and has tried to extinguish tribalism as a political force ever since. On the other hand, the major opposition parties – the DTA, the UDF and NUDO – have all tried to win support by railing against perceived Ovambo domination of Namibia. For example, Damara Chief and President of UDF Justus ǁGaroëb argued at the last election “the Owambos have been leading this country for very long. It is time for another tribe. This country belongs to all Namibians and not to the Owambos alone”. Whether you support SWAPO or the opposition parties has depended to a large extent on whether you find this kind of tribalism convincing.

Survey Data & Namibian Politics

Political scientists are interested in understanding why ethnic identities – your identity as a Otjiherero, Oshiwambo or Khoekhoegowab (Nama-Damara) speaker, for example – matter for individual identity and political party choice for some people and not as much for others. This question is what brought me, a PhD student in the United States, to Namibia last summer. There have been a number of surveys conducted by the NGO Afrobarometer since 1999 that have asked Namibians a question along the lines of “suppose you had to choose between being a Namibian and being a member of your ethnic group. Which would you choose?”. These kinds of survey questions can help us understand which factors – for example, education, income, or region – help predict whether someone in Namibia feels that their ethnic or national identity is more important to them. Similarly, we can use survey data to help understand why some people support parties that campaign on an ethnic basis such as NUDO or the UDF whilst others support explicitly non-ethnic and anti-‘tribalist’ parties such as SWAPO.

The data suggest that history, more than demographics, shapes the importance of tribalism in Namibia. Above all, ethnicity matters more for individual identity and voting choice in areas of Namibia north of the former Red Line.

Tribalism and Differing Colonial Histories

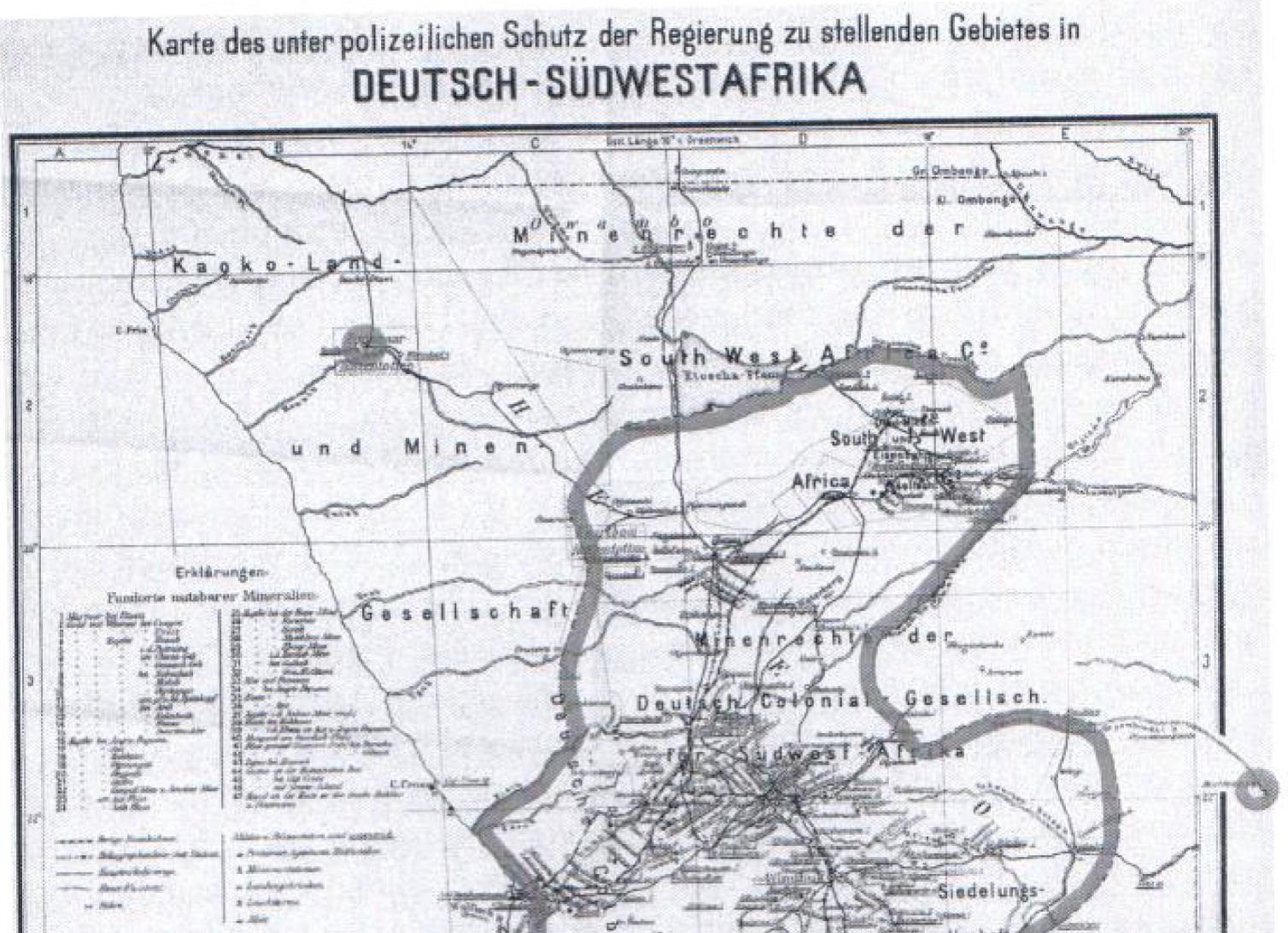

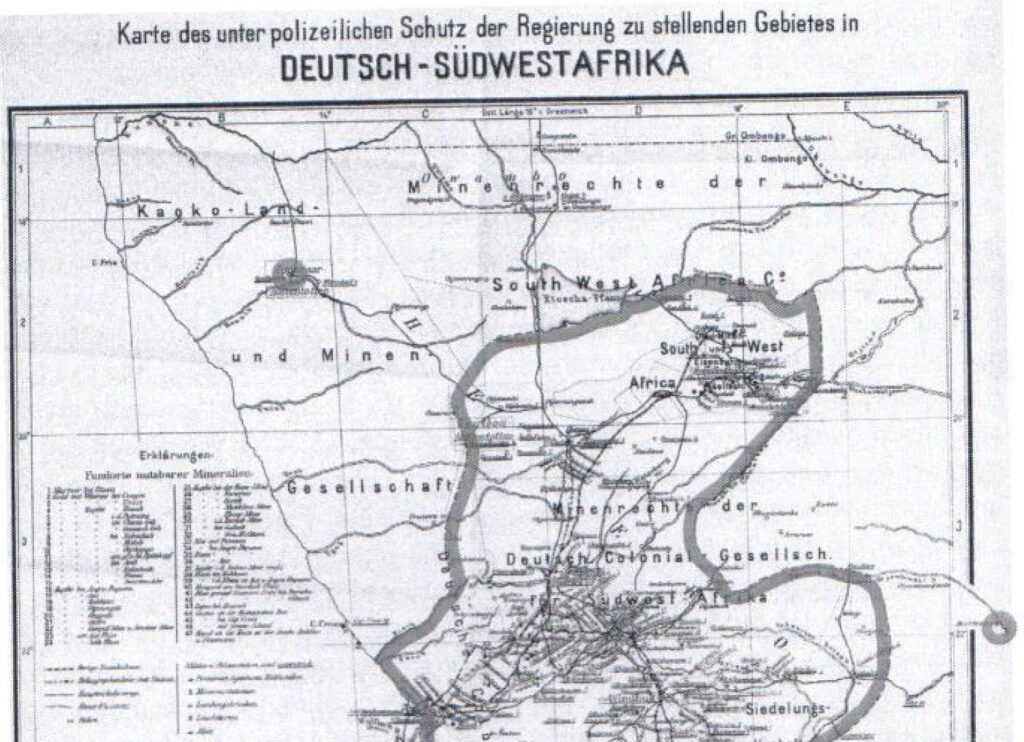

In 1897, the German colonial government created a veterinary cordon fence in the area near Etosha in order to protect their herds against potentially diseased cattle from the North. This fence formed the northern boundary of the Police Zone – the area of South West Africa under the direct control of the German colonial government. Later, the South African administration through the Odendaal Commission of 1963 deepened the division between the areas north and south of the veterinary fence. Areas north of the fence – the Red Line – became ethnic homelands. Your ethnic classification determined where you were allowed to live and what communal lands you could access. State-anointed traditional leaders were given a great deal of political power over their co-ethnics in these homelands. The ongoing existence of politically important traditional leaders and communal lands remain important factors that distinguish areas north and south of the Red Line in Namibia today.

To a surprisingly large extent, these different historical legacies still affect national identity and political party support today in Namibia.

Namibians located just north of the Red Line are much more likely than individuals just south of the Red Line to say that they would rather be identified as a member of their ethnic group than as Namibian. Ethnic parties also do much better north of the Red Line at securing electoral support. The DTA does much better at getting the votes of Khoekhoegowab speakers and Otjiherero speakers just north of the Red Line than just south of the former Red Line. Amongst Khoekhoegowab speakers only, the UDF is much more popular north of the Red Line and, amongst Hereros only, NUDO is similarly more popular north of the Red Line.

SWAPO on the other hand does very well at gaining the support of Khoekhoegowab and Otjiherero speakers south of the former Red Line – it gains approximately 37% of their votes. Yet, it only secures 22% of Khoekhoegowab and Otjiherero speakers north of the former Red Line. Ethnic identities and ethnic parties in Namibia today are therefore both stronger in former ethnic homelands.

If recent history is any guide, the competing visions of Namibia as One Nation and as a confederacy of different ethnic groups will continue to play out politically over the coming years. SWAPO’s vision for Namibia has successfully dominated the political landscape for sometime now, but its relatively weak support among non-Ovambo Namibians in areas north of the former Red Line suggests ongoing vulnerability to the charge of Ovambo favouritism. The issue of land reform will invariably re-ignite tribalism in Namibia as politicians such as Swartbooi and traditional leaders such as Justus ǁGaroëb seek to rally their co-ethnics to defend traditional land rights in former ethnic homelands. The political power of tribalism in Namibia will, however, continue to vary across communities north and south of the Red Line that have inherited very different colonial experiences and political institutions.