By: Erich Maislinger (University of Salzburg)

Originally Published 23 October 2020 [LINK TO ORIGINAL]

Bars of any kind are essentially social places, offering a non-committal getting-together of a variety of people. It must be noted, though, that not everybody has always had access to any bar. After all, bars are also environments where social hierarchies are reproduced, and sometimes challenged. With Namibia’s past in mind, it seems clear that the (poorly documented) history of such localities is often one of segregation. However, since independence, we can see that these racial and cultural boundaries are not as fixed as they once were.

Establishing Segregation

Segregation in drinking establishments in Namibia has its origin in the Brussels Conference of 1890, when European colonial powers (including Germany) decided to forbid the sale of any alcoholic drinks to indigenous Africans on grounds that colonialists believed that Africans could not drink responsibly. The German administration tried to implement laws to follow these policies, although not very successfully. Prior to the Genocide, laws were not always enforced very stringently, and even later, when there was more administrative capacity to enforce legislation, prohibition was never fully achieved.

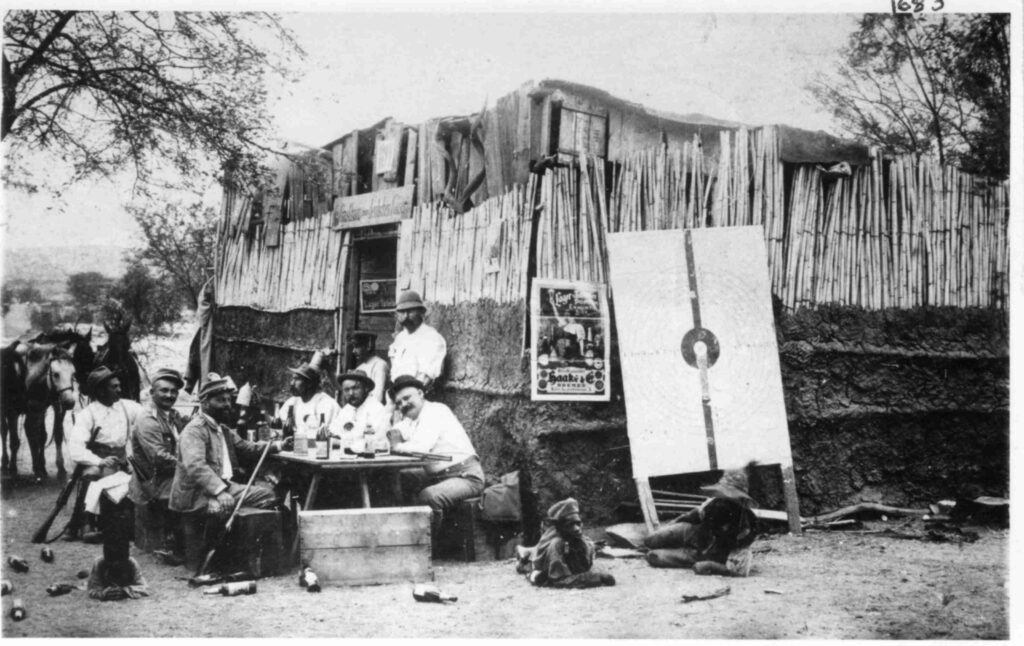

Also, the aim of general segregation from the Africans was just not possible at this point. An excellent example to underline this is the shown picture of one of the first “pubs” in Windhoek, which was called “Gastgestätte zum Deutschen Kaiser”. Photos like this one are rare, and compared to later ones, the setting is really different, because non-whites usually would only be seen as workers and not relaxing next to their “masters”. Of course, even bars which were frequented by both blacks and whites were still subjected to the power-politics of colonialism (the position of non-whites in this photo is already making this clear). Nevertheless, it took a long time for full segregation of drinking establishments to become implemented.

As the infrastructure of the German colonial cities improved, and administrative powers increased, the separation of whites and non-whites deepened. Gradually, if black and coloured Namibians wished to enter a bar, they had to be employees there. Unfortunately, not much is known about the daily lives of these people working in drinking establishments during the German colonial times. What can be said, however, is that many of these waiters and waitresses received alcohol from their employers as a means of payment, reward, or even bribery. These all technically contradicted the alcohol laws at the time.

Many bars also functioned as brothels, which was just one more reason why the administration tried to heavily regulate those places. While the high alcohol consumption among Europeans was not seen as a major problem at first, by the end of the colonial era, drunkards were threatened to be placed on the so-called “alcoholic-lists” (Säuferlisten), which meant they would not be allowed to buy drinks at a bar. As an illustration of drinking culture among Europeans during the German Colonial Era, by 1903, there was approximately one licensed drinking establishment for every seventy-eight whites in Namibia.

Though the Germans were concerned (at least on paper) with non-whites consuming European liquor, they did not really care about the home-brewing of traditional drinks (like Oshikundu, Omaludu, Tombo, etc.) in the locations. With the South Africans coming into power after the First World War, this would change.

Consolidating Segregation

Under the South African Administration, the culture of whites-only bars changed somewhat, as larger numbers of Afrikaners moved into Namibia and became patrons of these establishments. These relationships were particularly tense, especially in the years around World War II. The administration became very concerned about ‘Nazi activities’ believed to take place at German bars. Some ‘activities’ were visible and easy to control, such as photos of Adolf Hitler which were removed from bars; but others were harder ascertain. It was believed that celebrations of German war victories happened in the bars, and in that atmosphere of distrust and opacity, all kinds of rumors circulated. In Outjo in 1939, the colonial administration believed that some Germans might commit acts of sabotage or even an attempt a coup d’état. In the end, the threats didn´t turn out to be real. Overall, it was quite difficult for the South African administration to easily find out what was happening in German Hotel Bars.

The South Africans also sought to more tightly control all alcohol consumption among non-whites; this included both European beer and liquor, as well as traditional brewing in shebeens and cuca-shops. In Windhoek during these years, many police raids were carried out, the home-brews were destroyed, and black Namibians had to pay fines for illegal production and consumption of alcohol. As a result, many people started to produce and drink traditional brews outside of the city in the surrounding hills.

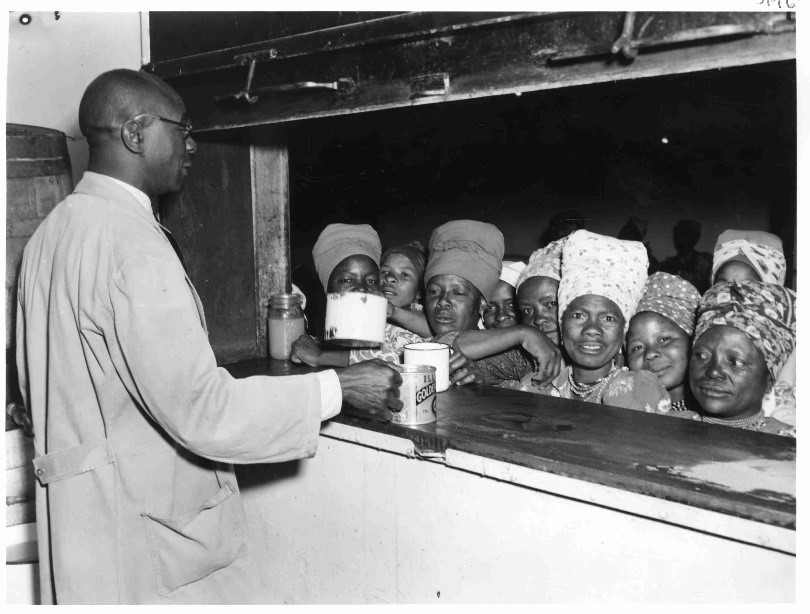

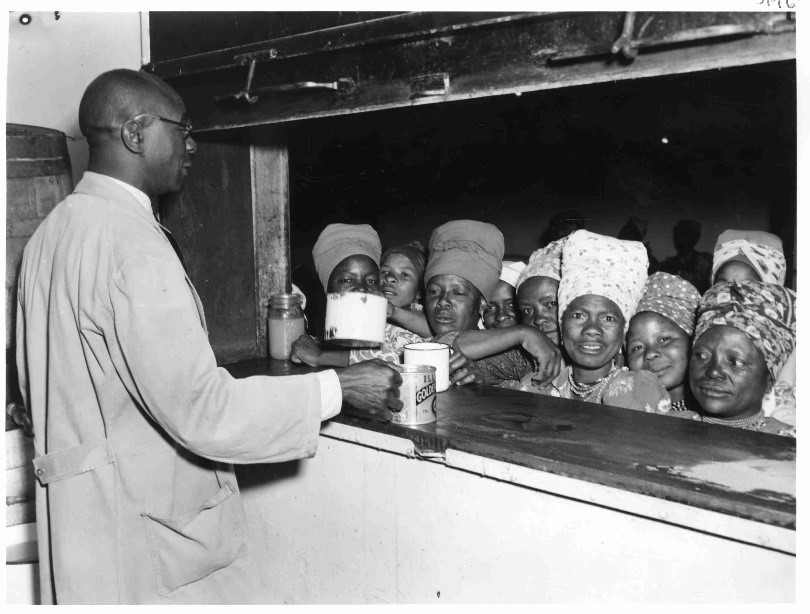

Even the South Africans recognised that enforcing complete prohibition was not possible. In the 1930s, the administration installed beerhalls in the Old Location; they have been in use in South Africa since the 1890s. Beerhalls were the only places where non-whites could drink alcohol legally. Here, beer with low alcohol content was sold, and revenue was used to finance the segregation locations. It is therefore no wonder that the non-white community was divided over these establishments. Fights over equal civil rights often took shape as fights over equal drinking rights, and many protests occurred at, or in connection to beerhalls. The most famous was the protests and shootings in the Windhoek Old Location in December 1959. Even though the planned removal from the location to Katutura was the primary reason for the protest, additional grievances included the administration’s prohibition of traditional brewing. According to a report of famous freedom fighter, John ya Otto, who witnessed what happened on this day, some people just wanted to drink their after-work beer while others smashed the windows of the beerhall as a sign of discontent. Ultimately, unlike the German bars, shebeens, and cuca-shops, beerhalls did not make it into the period of independence. When alcohol consumption was fully legalized in the 1970s, their story ended.

Slowly Crossing Borders

During the liberation war, many cuca-shops in northern Namibia served as places to have a drink for both people of color and sometimes whites (often soldiers). This caused difficulties for the owners, as one’s allegiance for or against the apartheid administration was contentious. Just before independence, some bars in Windhoek opened their doors, allowing people of different backgrounds to mingle together in a more relaxed atmosphere. The nightclubs ‘Namibia by Night’, located in Khomasdal, and ‘Midnight Express’ and ‘Club Thriller’, in Katutura, are worth mentioning. Up to the present, there still are not very many locales which are known for such a multicultural clientele, including local blacks, whites, coloureds, and foreigners. With that being said, even though bars in Namibia have historically been segregated establishments, positive changes have occurred since independence, and people are more often coming together to leave behind old ways of thinking. However, so long as the gap between rich and poor continues to grow, these multicultural spaces will retain a different sort of segregated exclusivity: one of class instead of race. This gap is the most serious border that has yet to be crossed, and which still divides Namibians.