By: Gary Marquardt (Westminster College)

Originally Published 28 October 2016 [LINK TO ORIGINAL]

Cattle are important to Namibia. However, their lives or deaths are not often seen to change the course of history. This story seeks to challenge that idea. In 1896, a brief but deadly cattle disease epizootic, rinderpest, swept through large parts of present-day Namibia; it was responsible for the death of approximately 50 to 95 percent of Herero cattle herds and upwards of 50 percent held by Germans. By the end of 1897, it was gone, a brief historical episode confined to interesting stories that happened long ago. Periodic episodes of rinderpest in Namibia happened in the early twentieth century but failed to take the lives of cattle like the earlier episode.

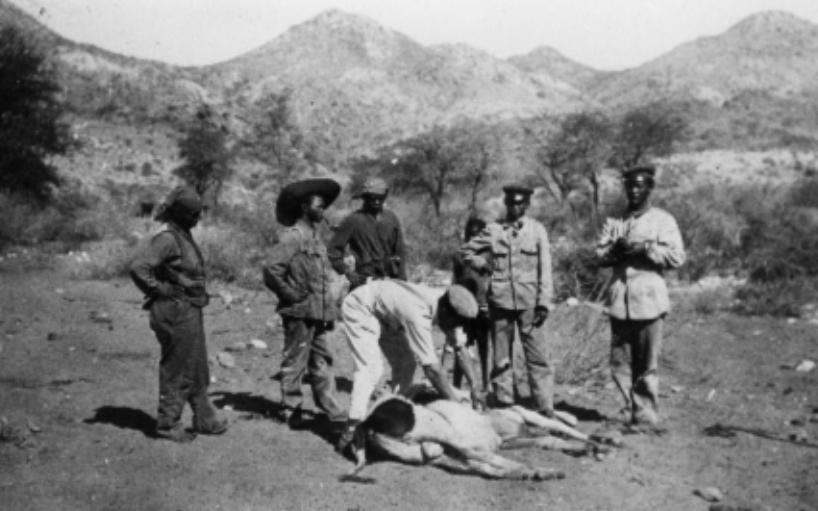

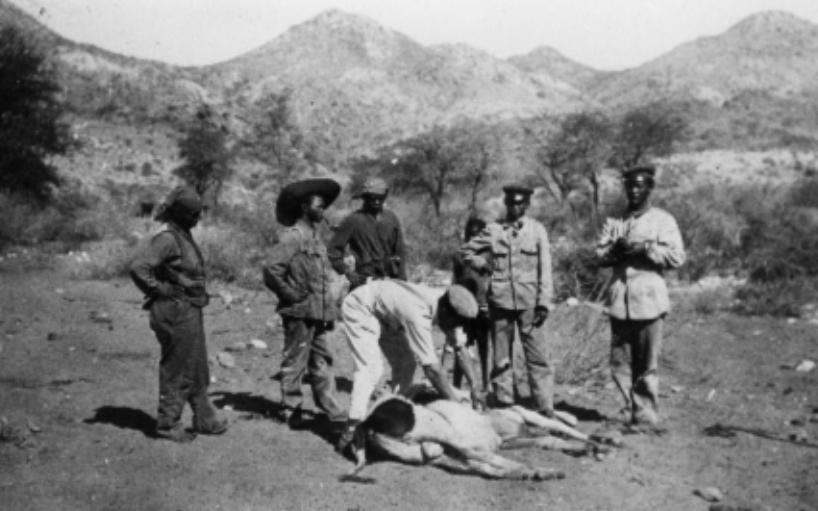

Fast forward eight years later to 1904, a date widely acknowledged as the start of the Namibian war and genocide where tens of thousands of people died at the hands of the German colonial state. What does the 1896 rinderpest episode have to do with this event? Not much, according to many historians and story-tellers of Namibia’s colonial history. However, if we look at what transpired between 1896 and 1904, one can see that the death of these cattle had a major impact on the relationships between Africans and German in the run up to war.

So how did this happen? What does a cattle disease have to do with a major war and the century’s first genocide? In short, everything that is foundational for making such conditions possible. Having travelled much of Africa since 1888, rinderpest made its final stop in Namibia less than a decade later. In its tour through the continent’s horn, eastern and southern regions, the disease claimed upwards of 90 percent of cattle, leaving African societies reeling in its wake.

In many of regions, rinderpest partnered with Europeans to successfully cement colonial control in the decade following the Berlin Conference. European missionaries and administrators referred to the disease a “blessing in disguise” as it took away the political, social and economic wealth of African pastoralists. Rinderpest took away African pastoralists’ ability to remain independent of colonial rule. It forced many young African men into migrant labor in the mines, farms, and towns, owned and operated by Europeans.

It had similar effects in Namibia. Many Herero men, for example, entered into employment with German employers. They served in the military and worked on farms, among other tasks. However, the German population was quite small during this period and so many Herero remained independent of this new European power in the country. Nevertheless, Herero independence was precarious at this time. For after rinderpest came a series of misfortunes further weakened Herero communities; they included drought, locusts, famine, and fatal diseases.

In the midst of these events Herero lost land, lots of land. As its cattle population decreased from at least 100,000 to approximately 25,000, so too did the land it needed for grazing. Cattle were the indicators of land wealth and ownership. They marked Herero land holdings by grazing on and thus domesticating it to their needs. With a significant number of their cattle now gone, Herero herders required less land on which to graze their herds; the process left land dormant and thus the environment began to change in two ways. Firstly, it changed as a result of gradually becoming overgrown, or undomesticated. Secondly, it was bought up and/or settled by German colonists looking to own land and suit it to their lifestyle. The Germans were keen to take up pastoralism as they noted how well Herero did in central Namibia. However, German settlement and development of the land drastically altered the way it looked before rinderpest.

Despite these setbacks, Herero maintained their historical pattern of breeding cattle, and brought back their numbers, wealth and power within a short period. By the early twentieth century, Herero-owned cattle had become numerous and attracted German attention. Herero had moved cattle back onto land formerly vacated in their absence. Their re-emergence challenged German efforts to marginalize Herero society and gain further control over their lands.

Such tensions led to disputes between Herero and Germans. Historians note that German civilians and military personnel often ill-treated their Herero neighbors and laborers, willfully miscommunicated to incite political tensions, and took land from existing Herero holdings without permission. The cumulative effect was a deteriorating relationship between the two sides.

By 1904, the die had been cast. Herero were not only growing their herds back to pre-1896 numbers, their political strength had grown as well. They were ready to assume land they claimed before the arrival of rinderpest. Meanwhile, German settlement in the region grew. Combined with other factors, there was little that stood in the way of the war or genocide between these two nations.

Cattle embody Namibia in its economy, cultural and political wealth; why shouldn’t we consider them as historical change agents? Without this tragic loss of herds to rinderpest, Namibia may not have witnessed the massive loss of human life through war and genocide that occurred in 1904. The disease put into motion the processes leading to the ultimate demise of Herero society as evidenced in the first genocide of the twentieth century.