By: Bayron van Wyk (University of the Western Cape)

ORIGNALLY PUBLISHED 28 MAY 2021 [LINK TO ORIGINAL]

On 18 October 1965, the statue of the Mayor-General Curt von François went up in front of the City of Windhoek headquarters. The newly constructed building was to coincide with the inauguration event to mark the 75th anniversary of the ‘founding’ of the city by Von François. In 1889 he had arrived in Namibia from a mission in West and Central Africa to encourage traditional leaders to sign protection treaties with the German Empire, which his predecessor Heinrich Göring failed to do. Although he had already signed a treaty with the Ovaherero chief, Tjamuaha Maharero, Göring failed to convince Goab Hendrik Witbooi (also known as !Nanseb Gâbemab) to do the same. Witbooi was one of the only chiefs in the south who refused to sign a protection treaty. For this he has been described as a revolutionary. Von François, however, regarded him as the greatest threat to German colonial ambitions in Namibia. Therefore, Witbooi had to be militarily crushed.

In the early morning hours on 12 April 1893, Von François launched a surprise attack on Witbooi at his mountain fortress of Hornkrantz, 120 km south-west of Windhoek. It is estimated that 78 women were killed and 4 more wounded by the Germans. While Witbooi himself and some of his soldiers escaped further south – eventually retaliating with an attack on the German agricultural station Kubub near Aus – the Germans would continue to hunt him down for years to come. On the present-day commercial farm Hornkrantz, now owned by the Cloete family, the graves of the Nama victims remain unmarked. Close to the kraal a small white monument stands to commemorate the dead. It was erected at a 1992 commemoration event by then-Prime Minister Hendrik Witbooi, himself a descendant of !Nanseb Gâbemab. When I visited the farm with the artist-cum-activist, Hildegard Titus, Mr. Cloete informed us that the site was under normal situations off-limits to the visitors interested in this history.

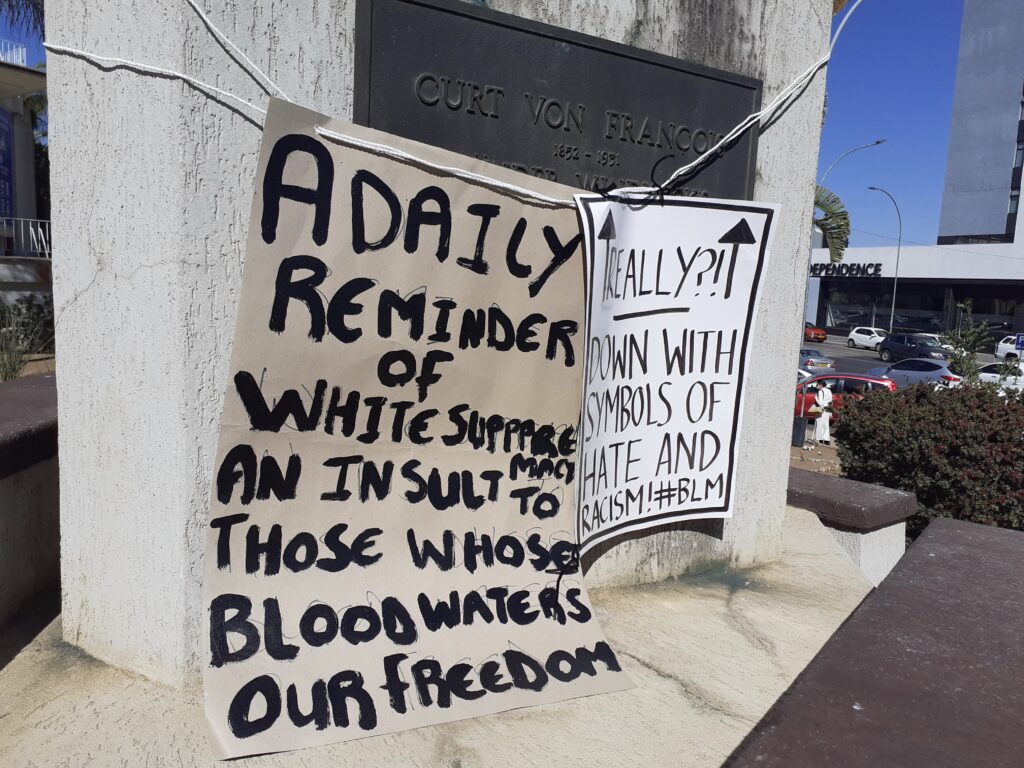

A lack of public awareness about the history of this battle and its brutal aftermath has led to an unjustified and ahistorical honouring of Curt von François – and even the Hornkrantz massacre itself – within modern Namibia. This is epitomized, perhaps, by the statue of Von François in front of the City of Windhoek. Hildegard Titus has been travelling throughout the south to create awareness of her #ACurtFarewell petition, which calls for the removal of the Curt von François statue (hereafter simply called ‘Curt’). The petition which was launched in June 2020 has garnered more than 1,500 signatures!

Echoing the sentiments of the Curt petition – on Namibia’s Youth Day – following the nation-wide COVID-19 shutdown, a group of young activists protested at Curt demanding for the statue’s removal. Dressed in their characteristic COVID face masks, the activists argued that it symbolized existing colonial systems of racism and sexism. As such, they connected their protest action to the global #BlackLivesMatter movement for racial justice after the brutal murder of George Floyd by American police officers, and the activists similarly wanted to draw attention to the extrajudicial killings of Frieda Ndatipo, Johnny Doëseb, Benesius Kalola and the Zimbabwean-born taxi driver, Tambouna ‘Talent’ Black. The former two men were tragically shot dead by Namibian Defence Forces (NDF), in their ‘Operation Kalahari’ campaign. This operation followed another (more) controversial anti-crime drive by the security forces, called ‘Operation Hornkrantz’. In a press statement released in early 2019, the NDF operation was criticised by Nama traditional leaders for its historical references to the brutal killings of their people by German colonialists in 1893. A decade later, the Nama would be systematically murdered and enslaved by this colonial force. According to estimates, 50% of the Nama population were killed in this genocide.

Concerning Windhoek’s #BlackLivesMatter protests, the City Spokesperson, Haroldt Akwenye, had the following to say: ‘I won’t mind it coming here’ and that the city was willing to work with activists ‘to change the look and feel of the city’. Several months after the petition was initiated by Titus, the statue still stands. Recently when I visited the site for my Masters-study research, I found two City of Windhoek institutional workers at the foot of the statue. When I asked what they were doing, they told me that they have been instructed to start with renovations on the front façade of the City headquarters. This will include a fresh coat of paint for Curt. It would seem that the demands of activists have received the backseat for the City Councillor’s priorities. This may soon change, however, as Job Amupanda, social activist as well as my former political science lecturer – was elected as Windhoek’s Mayor. The removal of Curt was identified as part of his political programme for Windhoek’s ‘Radical Transformation’, and recent statements by Affirmative Repositioning (AR) activists show that the push to remove Curt is gaining more traction than ever before.

The continued existence of the Curt statue points to the complexities of postcolonial Namibia – in which the colonial and postcolonial exists alongside each other – also evident in the high income and wealth disparities between blacks and whites. The situation is further exacerbated by an emerging black upper class. With many of the promises of the liberation struggle still not having had a trickle-down effect, activists are increasingly organising themselves and demanding sweeping changes. They want more social justice and for Namibia to properly decolonise itself – to rid itself of systematic racism, sexism, and become more economically just for all who live in it.